Midlife is when you reach the top of the ladder

and find that it was against the wrong wall.

Every year it gets harder to avoid the fact that I’m likely in the second half of my life. There was a time when it felt like every weekend was filled with 21st birthday parties. Then weddings. More recently, it’s been funerals. I’m also noticing a cohort of people who are about my age slip into midlife crisis. Typically these are people who forgot to be young when they were actually young.

It’s tragic to watch somebody who built a career or started a business finally achieve escape velocity only to immediately try to stop time, or even rewind - a young person’s car, a young person’s lifestyle, a young person’s relationship (often at the expense of the relationships that have supported them on the ascent), etc. It’s equally awkward to watch somebody who lived without responsibilities for too long suddenly realise that all their friends are now ten years (or more) younger than them. Meanwhile the people they used to know have moved on and have very different interests.

The important question that often goes unasked is: what are the things we can only do, have and be right now?

Be sad about the future, not the past

One of the things we all have to accept as we get older is that our body starts to fail. It could be our eyes (fonts need to be bigger), our ears (music needs to be louder) or our liver (nights out take much longer to recover from). Or, in my case recently, joints and tendons.1

Confronting knee surgery in 2021, I was warned that I might not be able to run again. I enjoy running so that was a dark thought for me, but slightly less so than it might have been because I’d run a lot while I still could. If I couldn’t run anymore at least I could look back fondly rather than with regrets. I’d miss what I no longer had rather than what I never had. I’d be sad about the future rather than sad about the past.

This is a useful aspiration. But even once we know, it’s surprising how hard we have to work at putting it to practise.

As someone prolific once explained to me:

The secret to having an amazing project to talk about today is to also have five other projects that won’t come to fruition themselves for weeks or months or years.

Not many people can multitask like that. And it’s contradictory advice because the key to making any one of those projects successful is dedicated focus. The people who solve that riddle are the ones we read about in biographies. The rest of us mere mortals can just ask two questions each day:

- What do we need to finish today, because the opportunity might soon pass; and

- What do we need to start today, because the time has finally come.

The depressing bit, and the reason these questions are so often so hard, is a double whammy: the things we need to finish often needed to be started a long time ago (the best time to plant a tree is 20 years ago) and the things we need to start won’t pay off for a long time (if ever) so they are easily deferred.

I wonder if advice like this is even harder to understand if you live in a city or in a place with a temperate climate. Maybe it’s easier in the countryside or closer to the poles, where the change of seasons are more explicit. The biblical advice about there being a time to plant seeds and a time to harvest (and a time to rest) is more obvious where failing to do those things in the right season means missing the window for another whole year.2

Make hay while the sun shines. Pick fruit when it falls.

We can only be each age once.

Let me photograph you in this light in case it is the last time

That we might be exactly like we were before we realized

We were scared of getting old it made us restless— When We Were Young by Adele

-

As they say, be kind to your knees, you’ll miss them when they are gone. Advice, like youth, probably just wasted on the young. ↩︎

-

Ecclesiastes 3:2, King James Bible. ↩︎

Related Essays

How to Scale

What a founder in one of the poorest areas in Kenya taught me about how to start and how to scale

The Plunge

Why do the most interesting bits of startup stories always get airbrushed out?

Head first, then feet, then heart

What could we be great at? What are we willing to take responsibility for? Combine those two things and maybe we can change the world!

Machines & Phases

There are so many different ways to measure a startup. It’s easy to drown in metrics. How do we separate the signal from the noise?

Unit of Progress

Be specific: Where are we going and what will it take to get there?

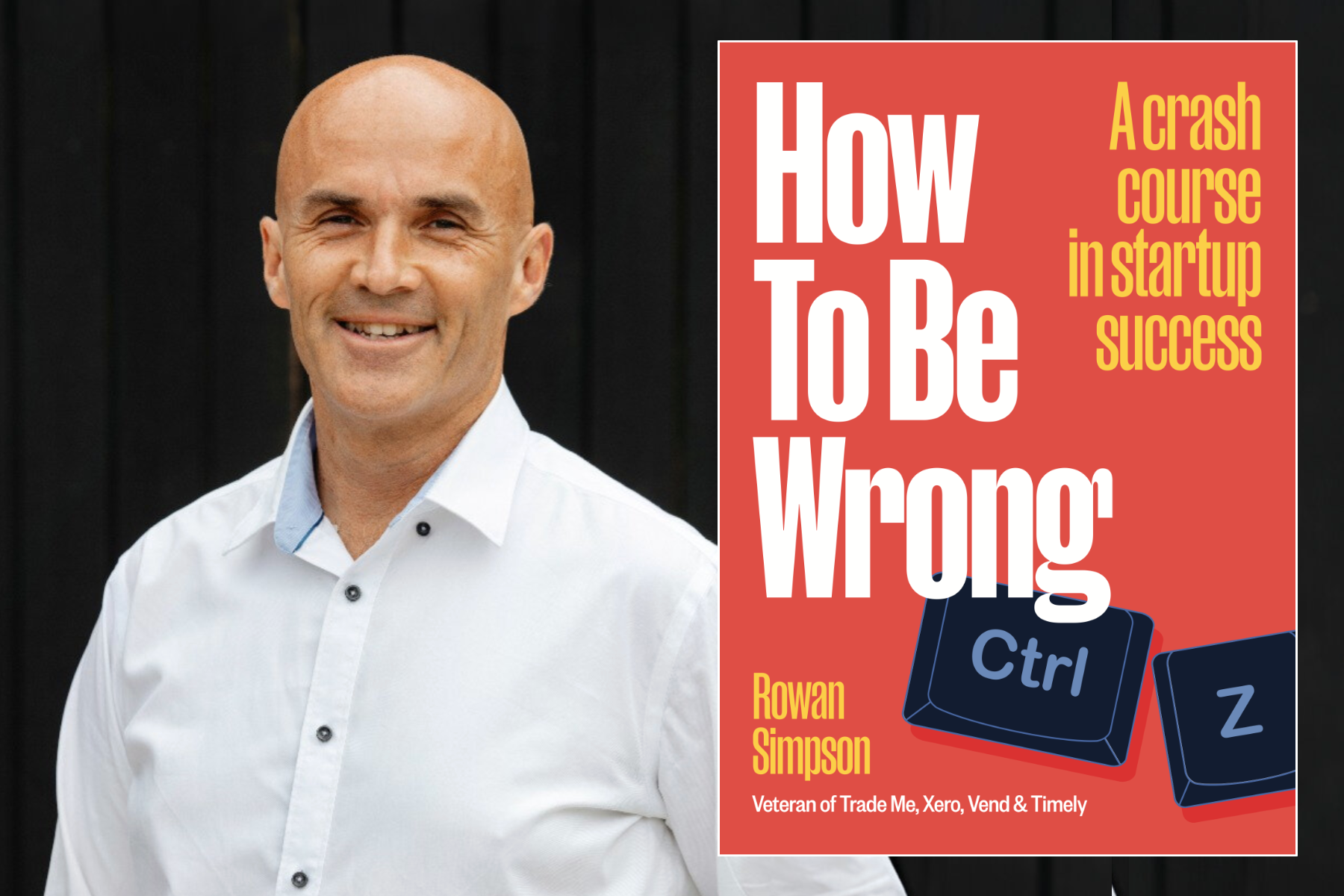

Buy the book