How can you change the world?

It’s tempting to focus on the big part of the question: the world. There is no doubt, the world is a big aspiration. But we don’t have to start there. We can, if we choose, start with the small part of the question: the change. Because, at least in the beginning, and probably for a long time after that too, any change we can actually make is likely to be small.

We can completely switch the question, just by asking it with a slightly different emphasis:

How can you change the world?

How can you change the world?

Perhaps if we focus on those two things we might find some way to actually change the world, rather than just wishing we could.

Make a dent

The potential of anything we build has two important dimensions: 1

- Width - how many people might eventually use it?

- Depth - how much value do each of those people get from it?

The combination defines the eventual volume of the work. This is what we mean when we talk about “making a dent”. People who make a wide but shallow dent are temporarily famous but often quickly forgotten. People who make a deep dent leave a mark, but are less likely to have a large audience. To be recognised and remembered we need to look for ideas that are both wide and deep, but those are very rare. Most of the time we’re choosing between one or the other, at best.

A common question to ask anybody struggling with this dilemma is: What are you passionate about? The underlying assumption is that change gets made by people who care. So uncovering the things we already care about the most will help point us at what really matters to us.2 It’s certainly true that when we don’t care about the things we’re working on or the people we are trying to help then we are unlikely to make a difference. And it is surprisingly easy to be distracted by other things that we should care less about, like how many people will notice. But it’s the wrong question to ask somebody who does care, generally, but is unsure in particular what to focus on.

Here are two alternative questions that I think are much more useful: What could you be great at? And: What are you willing to take responsibility for?

Wunderbar!

It’s easy to talk about being great. We might even aspire to be world class. But to achieve that, in a deep rather than wide sense, requires us to be very specific about both the niche that we focus on and what it means to be great at that particular thing.

For example, here are some niches from the sporting world, described simply:

Eight people (+ one additional small person shouting instructions) sitting facing backwards in a long skinny boat, pulling one oar each, in a straight line race in lanes over a 2km distance.

Or:

Person who can “put” (not throw!) a heavy metal ball (weighing 7.26kg for men, 4kg for woman) the furthest from inside a circle without stepping out of the circle in the process, with each competitor getting three attempts to record their longest effort, then three more attempts if they are one of the leaders after the first three.

Or even:

Person who can swim freestyle plus three other definitely not-freestyles over 100m each in succession the fastest, where each 100m is two lengths in lanes of a 50m pool, starting from a standing start on a small platform positioned at one end of the pool.

All three of these describe Olympic events where athletes from New Zealand celebrated success in recent decades.

If we dig a little deeper there are many other equivalent niches. For example, the world record for running a marathon dressed as a snowman is a tempting 3 hours 46 minutes.3 The world record for a three-legged marathon (i.e. two people running together, each with one foot tied to the other person) is 3 hours 7 minutes - depressingly, quite a lot better than my personal best time over that distance.4 Or, if you prefer larger team sports, the world record for a marathon in a five-person costume (a Chinese dragon, obviously) is 4 hours 21 minutes.5 But perhaps my favourite sporting world record of all is the 4x100m retrorunning relay. This is a relay race on a standard athletics track. Four runners each sprint 100m then pass the baton to the next runner. The unique factor is that they are running backwards. The world record attempt is available on YouTube and it’s hilarious and compelling - complete with very excited German commentary.6

You might not immediately agree that these are equivalent to better known sports. Many of them seem silly. But go back and read the descriptions of the Olympic events above and try to convince me that these are any less silly. Why is running backwards a joke on YouTube while swimming backwards is an Olympic event where the winner gets immortalised as a gold medallist? There is no logical explanation for that.

Retro-caring

It’s common to assume that once we care enough about something then we will do the work necessary to be great at it. But consider the opposite. We care about the things we are great at. Retrospectively.

This is a lesson I learned while watching Eliza McCartney win a bronze medal in the pole vault at the Olympics in Rio in 2016, going from an unknown athlete in an obscure sport to future star of an Air NZ safety video in one leap.7 I watched the final live, sitting with a group of New Zealanders that included senior sports administrators and funders as well as a number of other Olympians who had completed their competitions earlier that day. I think it’s correct to say none of us cared much for pole vaulting before that result. It wasn’t a sport that was given any attention or significant funding prior to that. But thanks to her performance, we quickly transitioned through mild confusion about the rules to become vocal fans chanting “E-liza-Mc-Cartney” (to the tune of Seven Nation Army by the White Stripes) over the course of a single evening. I realised that night we care about the things we’re great at, and that winning has a big influence.

Rather than starting with passion, the important question for all of us should be: what does it take to be great? Whatever niche we choose we can understand who is currently setting the standards, then think about what it will take to match or exceed their performance.

Infinite niches

Here are three more examples of specific niches:

Software to help you learn to play a keyboard, pad controller, or electronic drum kit

Or:

A customer research platform, using social network targeting to reach specific audiences

Or:

Premium freeze dried fruit snacks made from distinct New Zealand fruit (Gold Kiwifruit, Feijoa, Boysenberries etc)

All three of those examples describe young companies I’ve invested in: Melodics, started by Sam Gribben, which turns the music you love to listen to into the songs you love to play, with real-time feedback so you learn as you play; Stickybeak, a rapid consumer feedback platform now led by Anna Henwood, who help product and marketing teams to remove the guesswork and very quickly get specific feedback from real customers all over the world; and NaturKids, the brain-child of Bonny Slade, which has developed a unique range of award winning snacks foods and is exporting them to Southeast Asia. Time will tell if any of them turn out to be great businesses or not. I’m betting that they might.

Remember when Sir Paul Callaghan said he thought that the areas where New Zealand startups would find success would be weird and impossible to predict in advance? This is exactly what he was talking about. And yet, we continue to put a huge amount of time and money into trying to predict in advance. We have whole government departments working on it.

As an investor, why do I care about electronic drumming, public polling or delicious fruit snacks? The honest answer is: I don’t. Or, at least, I didn’t until I found people working on those particular things who aspired to be great, who understood what that would actually take and who were determined to do that work.

The good news is in business there are infinite niches like this for founders to pick from. The bad news is we can only choose one each. But the key is to understand exactly what it will take to be great in that niche. That’s how to make a dent.

The chicken & the pig

Consider a bacon and egg sandwich. Who contributes? 8

The chicken is involved, but the pig is committed.

We can ask the same question for each thing that we choose to work on: Are we contributing like a chicken or a pig?

We can be involved, like a chicken, on lots of projects at once. But we can only make an unbounded commitment, like a pig, to one thing at a time. By definition, as soon as our contribution is split between two or more things then the time and energy that we are able to give to each thing is diminished. Every successful project needs at least one person who is committed like a pig. If we can’t identify anybody who is all-in that’s a big problem.

This is a useful way for each of us to evaluate what we are personally willing to take responsibility for. Are we happy to just be involved, or do we want to have some skin in the game? It’s easy to say we care about something, but the proof is in how much time and energy we are prepared to spend on doing something about it, and how comfortable we are being accountable for the results that are achieved, good or bad.

Here are two simple but useful techniques:

Discontent

I used to think I had ambition - but now I'm not so sure. It may have been only discontent. They're easily confused.

Firstly, we can pay attention to the things that make us feel angry or frustrated. Often we just choose to live with these things. Sometimes we might offer to help when others step up to fix those problems. But being responsible means taking the initiative, not waiting for somebody else to describe the solution but instead having the curiosity and ambition to find it for ourselves.

It’s easy to look at something that seems broken and wish that it was different, but progress only gets made by the people who turn that discontent into activity. As Paul Bassat from Square Peg has described: “Boring people focus on the past, restless people focus on the future and content people focus on the present. The lucky ones are those who are content, but the restless ones change the world.”9

There is a curious phenomenon which I’ve seen repeated many times when startups raise capital: Getting the first investor to commit can be a struggle. This often causes founders to despair and wonder if it’s even possible. But then as soon as the first one or two investors are confirmed suddenly everybody who was tentative before is much more interested. Often rounds flip from undersubscribed to significantly oversubscribed very quickly. There is a reason why the first investor is often called “the lead”. Most investors want somebody else to follow.

Chickens live within the lines of other people’s solutions. Pigs realise they need to draw the lines.

We vs. They

A lot of times we're angry at other people for not doing what we should have done for ourselves.

Secondly, we can be conscious of the language we use to describe other people we work with and depend on. When talking about the things that need to be done, we can often neatly divide the world into people who mostly say “we” and people who mostly say “they”.

Think about how you describe the other people in your team and how your team describes the other teams in your organisation. Are they “we” or “they”? Keep an ear out for team members who talk about “the business”, as if they are not themselves in the business. This is silly. We are part of the business. We’re not stuck in traffic. We are traffic.

One of the keys to being a great coach is coaching the best players. When a team is great they make the leader look great too. And vice versa. Remember, it’s important to surround ourselves with the best people we can because our success is likely to be the average of everybody who is involved. Taking responsibility forces us to consider our leadership style. There are alternatives: we can be like a sergeant major, leading by example from the front, or like a coxswain, setting the cadence for others. My experience is that we can achieve a lot more as leaders if we don’t feel that we need to take all the credit ourselves.

Chickens belong to a team. Pigs build a team and get them all pointing in the same direction.

When we have the capability to be great, but don’t take responsibility, that’s idling. When we fully commit to the work, but don’t have the ability, that’s flailing. But when we combine those two things - when we fully understand what it means to be great at something and are prepared to make the sacrifices to achieve those results - then we have the opportunity to change the world.

-

These two dimensions are inspired by an article by Evan Williams where he listed seven dimensions to have in mind when evaluating any new idea:

- Tractability - how difficult will it be to launch a worthwhile version 1.0?

- Obviousness - is it clear why people should use it?

- Deepness - how much value can you ultimately deliver?

- Wideness - how many people may ultimately use it?

- Discoverability - how will people learn about your product?

- Monetizability - how hard will it be to extract the money?

- Personally Compelling - do you really want it to exist in the world?

-

Work on Stuff that Matters: First Principles by Tim O’Reilly, 11th January 2009. See also: Be Defeated by Greater Things. ↩︎

-

Fastest marathon dressed as a snowperson (male), Guinness World Records. ↩︎

-

Three-Legged Running World Records, Record Holders. ↩︎

-

Fastest marathon in a five-person costume, Guinness World Records. ↩︎

-

World Record, 4x100m Retrorunning, Rückwärtslaufen mit Weltmeister Roland Wegner, YouTube. ↩︎

-

Actually, seven leaps in the final, following on from six leaps in qualifying which included failures at her first two attempts and a mistimed run-up on her third and final attempt at that first height which didn’t seem to bother her at the time but caused a lot of anxiety for those of us watching. ↩︎

-

The Chicken & The Pig, Wikipedia. ↩︎

-

Paul Bassat, Twitter, 10th December 2016. ↩︎

Related Essays

World Class

The expression “world class” gets casually thrown around, like a frisbee at the beach. But what does it really mean?

Most People

To be considered successful we just have to do those things that most people don’t.

Anything vs Everything

How do we choose what to focus on, and have the conviction to say “no” to everything else?

Flailing

Here is some unusual advice for people working on a startup, or thinking about it: swim.

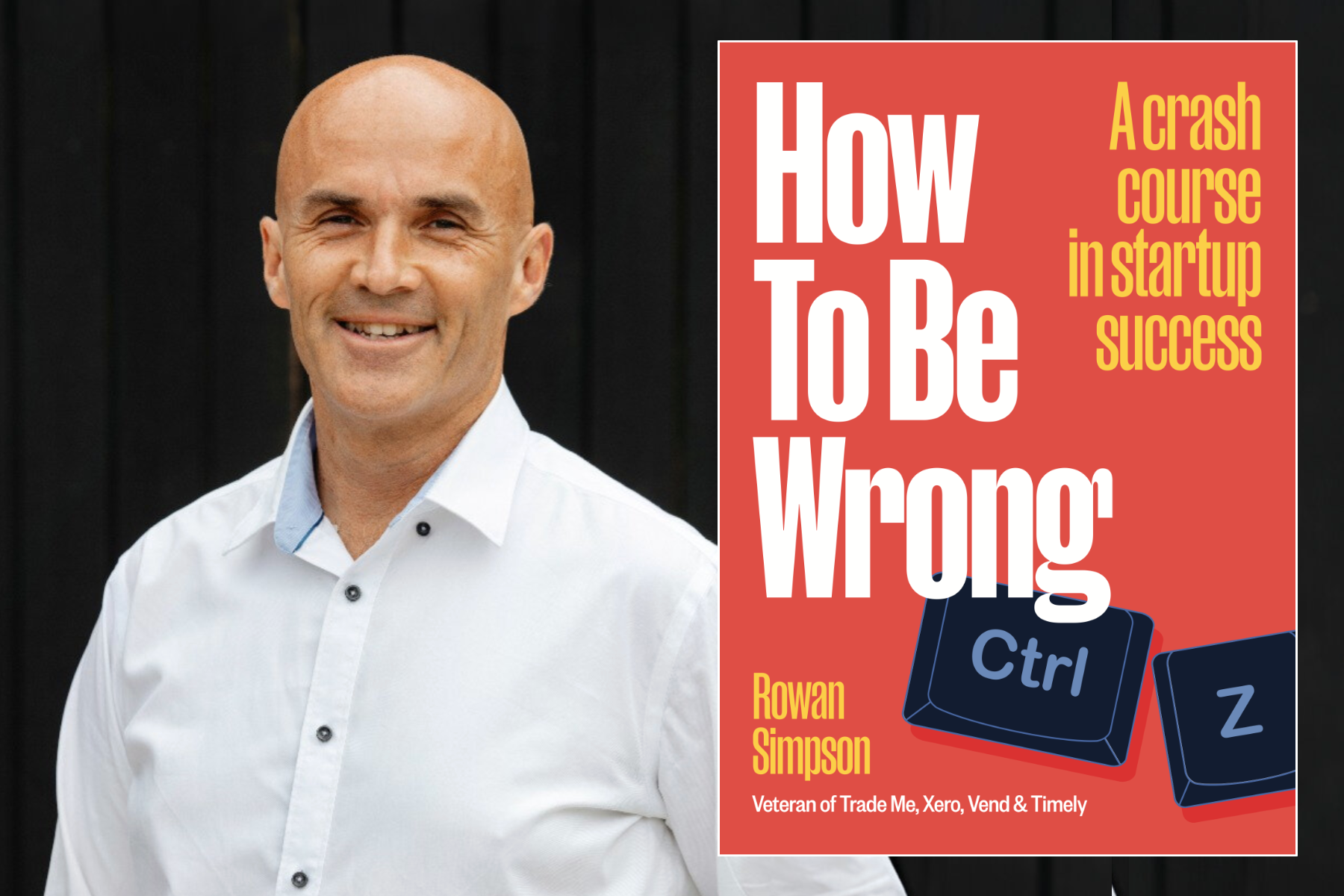

Buy the book