A startup that goes well can be very lucrative. How do we ensure that all the people involved in creating that outcome get their fair share? It’s a question that can soak up a lot of time for founders and investors. To answer it we need to go deep into the weeds of startup compensation, options, capital gains and tax.

Reward

There are many ways to get paid when we work on or invest in startups. We should think about which of these to optimise for in the short term and long term.

Salary or wages. We can get paid directly as employees. This could either be a fixed salary, or an hourly rate. The obvious advantage is the amounts are agreed and documented in advance and we always get paid (at least as long as the startup stays in business). However, because the amounts are fixed, there is no upside if things go really well.

Commission. We can get paid a percentage of revenues. Sales people are often paid a commission, based on sales made. There are many possible structures, depending on how easy it is to attribute sales and revenues to a specific person or team. A variation of this is where everybody on the team is paid a percentage of total revenues – as an end-of-year bonus, for example. This is also how partnerships work. Successful sales people can earn more, and get paid immediately (notably before shareholders). But there is no guarantee we’ll make as many sales as we need – especially in the early stages things are often slower than we’d hope.

Shares. Last but not least, we can own shares in the company. If the startup becomes a high-growth company the value of the shares can increase significantly over time.

However, we have to invest cash up front. The one (and only) way to acquire shares in a company is to buy them. You might read that and say: nonsense – sometimes people working on startups get given shares. Let me explain what I mean. When a new company is incorporated shares are issued to everybody who invests the initial capital. These are typically very small amounts. At the beginning a startup is only worth as much as the capital invested by first believers. Later other investors can buy shares, either from the company when new shares are issued in an investment round or from an existing shareholder who is willing to sell them. However or whenever we acquire shares, it always involves an investment.1

It can be many, many years before we get a return on that investment. And there is no guarantee of any return at all - in fact the average startup returns nothing. There are two (and only two) ways to get a return. The first is when the company pays dividends to shareholders from profits. That is exceptionally rare for startups, because they usually take many years to become profitable and even then usually prefer to reinvest those profits in further growth rather than make payments to shareholders. The second is when the shares can be sold to somebody else.

Gonna make you sweat!

Perhaps it seems like something is missing from this list. It’s true there is one thing, which I’ll get to shortly, but it’s probably not the one you’re thinking of.

People working on startups commonly and incorrectly assume that “sweat equity” or “options” allow them to become shareholders without investing up front. I’ve found both of these things are widely misunderstood, by employees, founders and investors.

I’m not an accountant and definitely not your accountant, so if you have been given “free” shares or options in return for work on a startup stop reading this and instead get good advice from somebody who is. Start by asking them how much tax you will pay and when.

Sweat equity. In simple terms, “sweat equity” is when we are paid for the work we do in shares rather than cash. That’s possible, but it doesn’t make them free. New Zealand’s Inland Revenue treats the value of the work you did as income and expects tax to be paid immediately, whether you were paid in cash, shares or magic beans.

The obvious downside is that it could be a long time before the shares generate any cash returns. A better way to think about this type of transaction is to imagine we are paid cash (and pay tax on that amount) then immediately invest that cash to buy shares at the current price.

Options. On the other hand, an “option” is a contract that gives us the right to purchase shares in the company in the future, for a price that is agreed up front.

There is a lot of jargon to learn in order to understand options. Typically, they have a “vesting” period. This is the time between when the options are issued by the company and when they become unconditionally owned by the employee. Departing employees usually forfeit any unvested options. Sometimes there are additional performance criteria attached to vesting. For example, sometimes options vest based on milestones rather than time.

Once options are vested employees can choose to “exercise” them at any point before the “expiry” date. That means, paying the company the agreed price (the “strike” price) in return for the agreed number of shares. Remember, shares always cost money.

In the case of options New Zealand’s Inland Revenue treats the difference between the price you pay (usually a small amount) and the value of the shares you get as income, just like a salary, and expects tax to be paid on that amount. The advantage of options compared to basic sweat equity is that they allow the tax bill to be deferred until the point where shares can be converted into cash. But that comes with not insignificant complexity: typically options have a very low strike price and a long-dated expiry (10 years, say), meaning that once options have vested employees can wait until there is a transaction, then exercise them and sell them immediately. The tax bill in this case is on the difference between the strike amount and the sale price, which can be substantial. But at least employees have cash on hand at that point to cover that expense.

Sweat equity and options are not a way to give employees free shares, they are just salary and incentives disguised as shares, with corresponding tax treatments that apply.

Pay to play

What is the other common way of getting “paid” to work on a startup? It’s actually the reverse: it’s volunteering time or even paying to work on a startup. This might sound incredible,2 but it happens all the time. For example, whenever a potential investor meets with founders to give their perspective and advice, without receiving (or expecting) any payment. Or, following investment, when an investor becomes an unpaid director or advisor to the founders during the early stages. They have effectively paid the company to hire them. Immediately following investment the biggest constraint is forward momentum, so the best option for investors is to focus on increasing the value of their shareholding rather than on their hourly rate. This is also common in the non-profit sector - e.g. where we might donate both time and money to an organisation to help them with their work.

This is what I mean when I say the best founders choose their investors. Smart investors are prepared to invest handsomely in the opportunity to work with the best founders: generally a little bit of money and a lot of time. And it’s usually the time that makes the biggest difference. Unfortunately most founders optimise for money. This creates a race to the bottom for investors (especially those running venture funds) as everybody competes to offer founders more and more cash on more and more generous terms. What gets squeezed are the potential returns and, more importantly, the time that investors can put into helping to make the outcomes great for everybody.

Align

If you write a song that’s recorded umpteen times, the income will last your lifetime plus copyright, which is 70 years.

But if the songs take shape in the studio, over late nights and conceivably the odd spliff, how do you decide who has written what?

How do we align incentives in a startup between shareholders, who invest time and money hoping for a payback far in the future, and team members, who are paid a salary and/or commissions? This seems like such a simple question, but all of the obvious answers are a mirage. If only I could get back all the days I spent wrestling with possible solutions while working on Vend and Timely, and many other similar ventures since then.

While there is no perfect answer, I still think it’s important. When startups go well they can go really well. For example, when Xero listed in 2007 the whole company was valued at $55 million (and there were a small group of us who invested prior to that at lower valuations). Today it’s worth billions.

Ideally, the team who does the hard grind day-to-day to grow the company should share in the upside, rather than having that value captured entirely by shareholders who contributed capital. While it might, on the surface, seem contrary to their own interests, smart investors understand that getting this right is often a key that can help to unlock that upside in the first place. For example, it’s common for venture investors to insist on 10% or more of the company to be set aside for allocation to employees via an employee share ownership plan (ESOP). The question then is just how to manage that allocation. But the details get devilish very quickly. Often because of tax.

The first problem is that shares have a cost and we can’t just gift them to team members without creating an immediate tax liability. Meanwhile the payback could be many years in the future, if at all. Nobody wants to pay tax on income that may never actually be received.

When I began investing in startups it was common to solve this using an employee trust structure, which effectively gave employees the benefits of shareholders without requiring them to invest cash up front. However, there is no such thing as a free lunch – these schemes were very expensive for companies like Vend and Timely, because of the tax that was paid up front on behalf of employees; because of the cost and complexity of administering them; and because of the large amount of time spent explaining these schemes to employees. I personally sank a significant amount of time on this, especially at Vend, which would have been much better spent growing the business. For all these reasons less lucrative, simple options schemes are now more popular.

An alternative, which we used subsequently at Timely, is called “phantom equity”. This is just a fancy name for a cash bonus which is paid in pre-agreed circumstances, such as when a startup is floated on a stock exchange or sold outright. The tax position on these is cleaner, or at least more easily explained: employees pay tax on the bonus when it’s paid, just as they would on any other salary amount. Perhaps as an indication that I’d completed a full lap, this was a throwback to the exact pattern we used to compensate the team at Trade Me following the sale to Fairfax.

Aligning incentives is complex. Employees don’t and can’t benefit from the gains like investors do unless they invest cash up front like investors do. That doesn’t seem fair. The real problem, if we address the elephant in the room, is that in New Zealand there is no capital gains tax on investments. Everywhere else in the world investors expect to pay tax when they sell shares for a profit, and that just gets priced into valuations and stock option calculations. Meanwhile we turn ourselves inside out trying to create schemes that don’t create big liabilities for employees. It’s a real handbrake.

There are, of course, two possible solutions: remove the tax on employee gains, or impose a tax on investor gains. Occasionally startup founders or investors, or other people in the ecosystem, agitate for special tax treatment for startup employees, but they are always curiously quiet about capital gains tax for startup investors. I’ve also yet to see any proposal that doesn’t just simplify to “we’ll just pay less tax, kthxbai”. There is always a frustrating lack of detail in these proposals about how this would be justified and explained to other taxpayers, who would be left covering the difference. Perhaps we think these incentives would create more highly paid jobs or more profitable startups that contribute income tax back to the economy. Or perhaps they would increase productivity, because employees working on startups would be more motivated. If we believe those things are real then let’s spell them out. And quantify them, rather than just putting our hand out. I’m not convinced they are real.

On motivation, specifically, my experience has led me to believe that a share ownership scheme spread across a workforce is not an especially effective way to motivate a team. In fact, it can be counterproductive. I’ve observed situations in which employees discounted the value of their shares to zero because they weren’t sure they would ever be valuable, and in some cases were still frustrated to get a big tax bill on exit. So the shareholders were left with the worst of both worlds: an expensive scheme that didn’t really change behaviour.

When there is a big exit, rewarding all of the people who have made that possible is important and delightful. But I’ve learned that the thing that really motivates people is a company with a purpose they believe in, work that they find meaningful and colleagues who support and encourage and challenge them to be better.

-

Maybe we inherited startup shares or won them in a late-night poker game, but even in those contrived cases somebody bought them before gifting them to us. ↩︎

-

Or as we might say in NZ: fairly interesting. ↩︎

Related Essays

Building An Ecosystem

How can we build an ecosystem of innovative technology startups in New Zealand?

Diworsification

A portfolio approach to early-stage venture investment doesn’t really help and probably hurts.

Discomfort

How can understanding our relationship with pain help us conquer challenges?

Show Me the Money

Trying to decide how to fund a startup? It’s important that we ask the right questions.

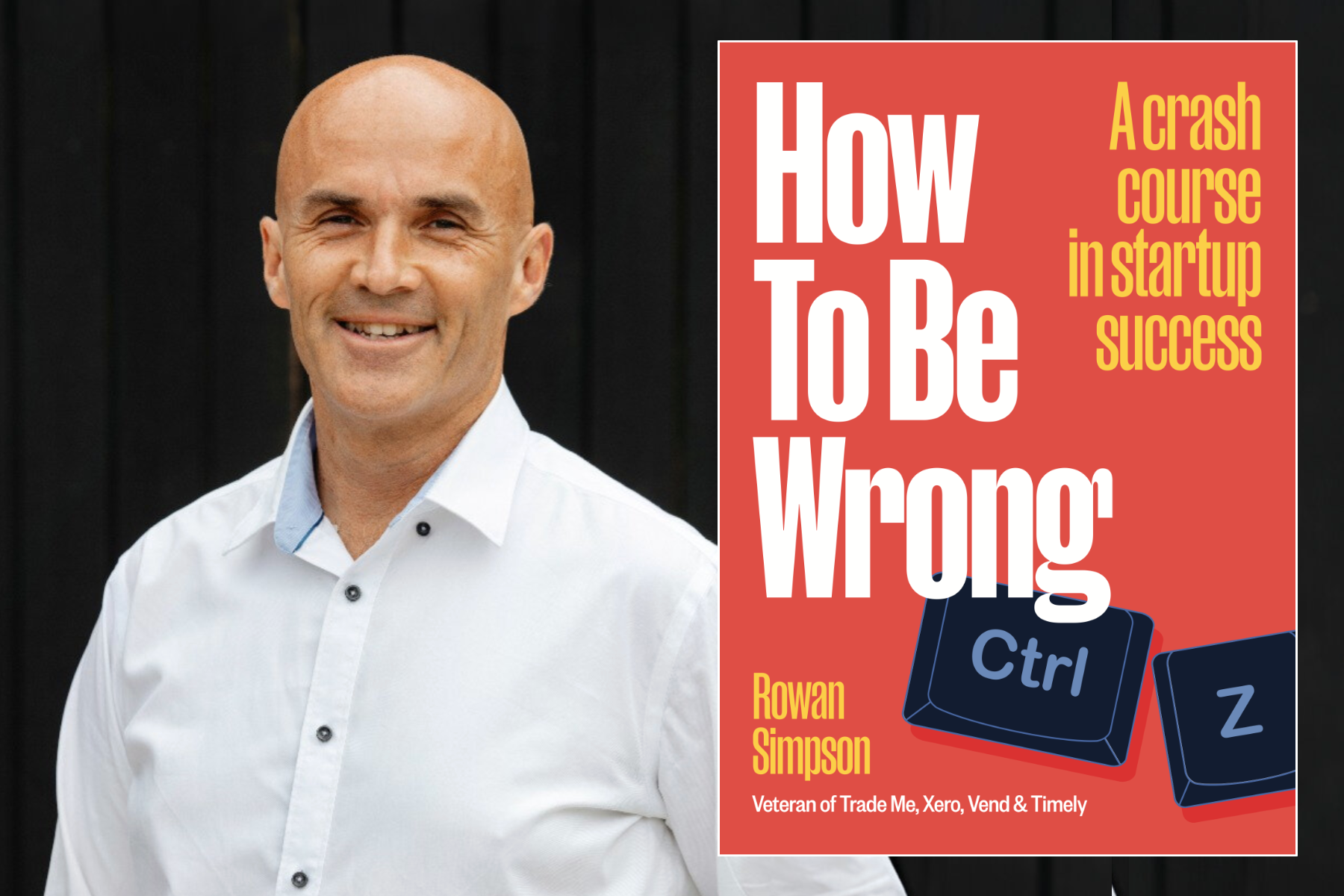

Buy the book