Warning: The first two sections of this essay might trigger an angry feeling. Please read all the way to the end before drafting your letter to the editor…

Build

What do we gain and what do we lose when we treat the world as binary?

Teams building new technology need two types of people.

Some people are heads down. They ask: How does this machine work, on the inside? They think about the aspects of the product that most people never see. They wonder how it’s made and how it could be improved.1 They have a deep technical knowledge and an ability to think in algorithms or production lines. They worry about performance and efficiency and optimisation. They think about engineering. They generally prefer to work by themselves, and usually know when they have done great work, without having to be told. They can sometimes struggle to understand that not everybody is an expert like them, and be dismissive of aspects of the product that seem to them to be simply aesthetics.

Others are heads up. They have a different question: How do real people use this? They think about the aspects of the product that people see and touch and interact with and beyond that to how this fits into the broader tasks people using it are trying to achieve. They can empathise with people, and often end up leading product teams.2 They worry about the look and feel. They think about the customer experience. They generally prefer to work collaboratively, and like lots of feedback to feel reassured they’re on the right track. They can sometimes be naive to the complexities of implementing something that looks simple on the surface, and ignorant to the trade-offs that their design decisions impose.3

Everybody working in a technical role should know which of these two jobs they do best. When we hire technical people we should be clear in advance which type we need. A great team has a mix of both.

Believe

With no disrespect to either Ms Myers or Ms Briggs,4 it sometimes feels like there are basically only two types of people:

Some people are fact-based. They focus on what they can understand and measure and prove. They ususally need the confirmation of feedback loops to give them confidence that they are making the right choices. The problem is that this fundamental insecurity can easily tip over into paralysis (“what if there is a better option?”) They still need something to prompt them and compel them to act, otherwise they never have a hypothesis to test.

Others are faith-based. They focus on what they feel and believe, and what intuitively seems right. They don’t need “facts” and “experts”. Instead, they rely on instincts and hopes. It’s important to differentiate between these two things. It seems reasonable to trust our own instincts. If we don’t, it’s unlikely that anybody else will. And they are often correct. That trust shouldn’t extend to blind faith. Hope is not a method. it’s generally just wishful thinking.5

Because there are weaknesses with either approach, there is obviously a place for both. But problems do seem to occur when these two opposing approaches overlap. Many of us think we are fact-based but then we also dismiss evidence that we don’t agree with or which contradicts our worldview (a.k.a. the things we believe or need to be true for some other reason). It’s difficult to not be defensive about our opinions or our previous positions. It’s easy to believe we are fact-based.

As I’ve been frustrated to discover many times, it’s ultimately futile to argue about specific facts with somebody without first confirming that is what they are basing their decision on, like arguing evolution with a creationist. Heresy in the wrong company is no joke! Likewise, it can be infuriating for somebody with strong opinions to work with others constantly questioning their judgement and wanting them to back up gut feelings with constant measurement.6 It’s so much faster to skip that step.

For the sake of our collective mental health it would seem that like minds need to stick together. But we’d all be worse off if we did.

I believe it’s possible to bridge this gap, but it’s not easy. To become more faith-based we need to learn to trust our instincts more, stop questioning, stop doubting and stop waiting for evidence before acting. To become more fact-based we need to develop the confidence to change our mind when presented with a better option, then work over time to make that a habit.

Either way, the important thing is to understand ourselves and the people we work with. If we do that we increase our influence and save a lot of frustration.

Split the difference?

Wearing a watch doesn’t make you a punctual person. But it gives you the information you need to be one, if that’s your wish.

Simple binary categorisations are enticing. For example, see above!

Usually, in each of our minds, there is one “correct” box and one “incorrect” box, and the world would be so much better if everybody could see that. But it’s more helpful to think of these things as a continuum, and to realise that there are always trade-offs.

For example, consider flexibility. Especially as we get older, who doesn’t wish they were more flexible? But rigidity and flexibility are two ends of a continuum. Both qualities have pros and cons. Being hyper-flexible is just as dangerous and physically limiting as being hyper- rigid. For some reason, flexibility is a quality with positive associations, while rigidity is not.

More examples are everywhere we look, once we understand the pattern:

Small vs. Large. Offence vs. Defence. Young vs. Old. Urban vs. Rural. Rockstars vs. Roadies. Masculine vs. Feminine. Web vs. Native. Left vs. Right. Seam vs. Spin.

When we put ourselves at the extreme end of any continuum, and boast about the benefits of that position, then we are very likely also compensating for some of the extreme downsides associated with that position. It can seem the sweet spot is in the inoffensive middle. But that might not be true either. In the middle the positives and negatives are likely both lower than they would be if we got off the fence. The reality is most things are complicated. The more we know about them the less simple they become.

Why can’t you see that?

-

John Gruber has a nice way of describing this, in a post about Objective-C.

He said:

There are some good programmers who view their source code as their product. The source code they write is, in their minds, the thing they are crafting. And if the source code, by nature of the language itself, is ugly, that’s a non-starter.

There are other good programmers who view the app they are creating as their product. The app is the thing they are creating and the source code is just a part of the process. It’s the difference between crafting code and crafting apps.

I would argue that both of these fit into the “Heads down” bucket. There is another level: those who view the things that other people do with their app as the product. ↩︎

-

As I heard Eric Ries say once, the career path of a heads-up developer is:

- Write software

- Lead a team of people writing software

- Manage people who lead a team of people writing software

- Advise people who manage people who lead a team of people writing software

-

How not to pitch a venture capitalist, by Ali G, YouTube. ↩︎

-

If you don’t know what “type” you are, but are tempted to take a test to find out, then by my simplified categorisations you are probably mostly fact-based. Otherwise, you’re probably mostly faith-based. ↩︎

-

Hope Is Not a Method: What Business Leaders Can Learn from America’s Army by Gordon R. Sullivan. ↩︎

-

Goodbye, Google, by Douglas Bowman, 2009. ↩︎

Related Essays

We Are Still Divided

The world is still divided, between you and me, baby, you and me.

Most People

To be considered successful we just have to do those things that most people don’t.

Monochrome

What can rugby teams and rowing squads teach us about building and managing diverse teams?

How to Get Old

We only get to be each age once. How many will we waste trying to be something that we’re not?

The Far Side of Complex

How do we get beyond complexity?

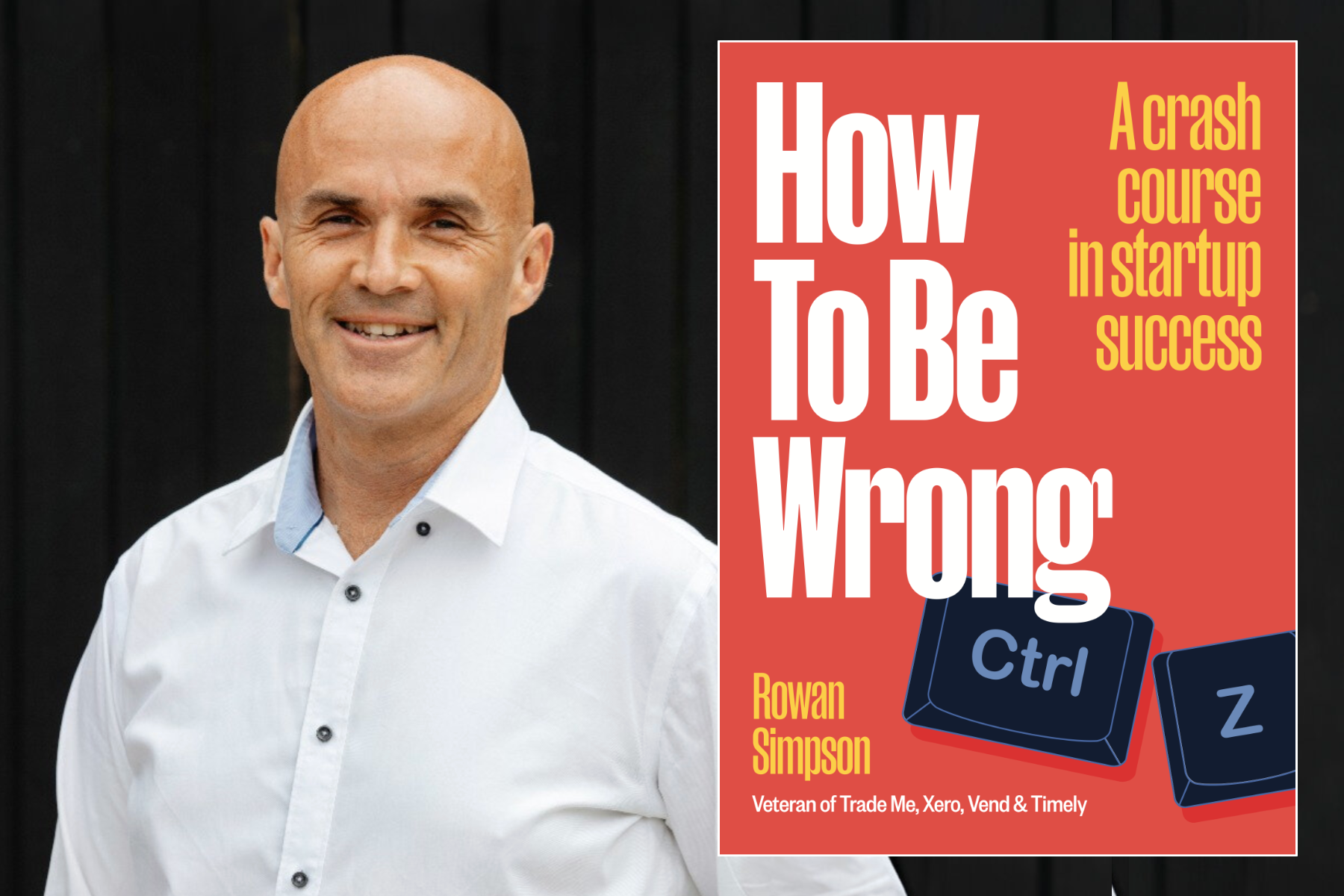

Buy the book