I’ve had the privilege of working with some interesting people over the years. But one of the most interesting was a colleague from way back in the day, when I was working as an IT consultant in London, in the early 2000s.

He was also a Kiwi, but had been in the UK for so many years the distinction was starting to get blurry. He had a long history of short software development contracts, which gave him the benefit of never really needing to get personally invested in the things he was working on, and provided the perfect outlet for his delightful cynicism.

The new new thing for our team back then was Microsoft’s .NET framework and associated development tools. Having recently come out of the first phase of Trade Me, where we were constantly wrestling with the limitations of VBScript, it was an absolute breath of fresh air to me. But every time I would get excited about a new aspect of the language I’d understood, or the potential to do something significantly better within the applications we were working on, he would quietly chuckle and explain to me that it actually wasn’t new at all but just a reinvention of an old idea that he’d seen before, back when computer screens were 40x25 ASCII characters and the font could be any colour you liked as long as you only liked green on a black background.

I’m making him sound like hard work, but actually I really enjoyed his company and the work we did together. He always took the time to explain, to put things in context and to make me think harder.

As it is with software development, so it is with self-help, it seems. So humour me while I channel my former workmate…

Suddenly everybody is excited again with the idea of less.1 The most celebrated business owners are the ones who implement four day working weeks. Every item in our house is required to spark joy, or be sent to the charity shop. The ideal diet is strictly plant-based (and it’s not enough to eat that diet ourselves, it’s also very important that we try to convince everybody else we know to do the same, or at least acknowledge their inferiority to do if they choose not to). The perfect inbox is empty. The best meeting is one we don’t have. These might feel like new ideas, but they are really just attempts to solve a very old problem. After all, life is apparently short,2 so we shouldn’t waste it on people or things that distract us from enjoying it, right?

Ironically all of this is a lot to take in and constantly worry about. And for most, I assume, exhausting!

Here is a much better question to ask, I reckon: What is enough?

If more people asked that question in advance, then perhaps there would be far less demand for minimalisation and de-cluttering later?

The problem with less is you can usually never get there, and it’s often fleeting on the rare occasions you do. The cake, as they say, is a lie. But the beauty of enough is that it is, at the same time, seemingly un-aspirational, and yet still elusive.

I mean, if you have enough then you can justify backing off, taking your foot off the pedal and enjoying the view. But so few people do that - especially, it seems, those who we consider most successful.3

For many having enough is a dream. But for those who actually don’t have much, life is a struggle. To even want to have less is a massive privilege.

Perhaps, like my old colleague, rather than getting excited about these things and immediately assuming they are solutions, just because they are new and fashionable, we should think a bit harder about what problem we actually need to solve, and how these patterns have provided a solution to them in the past.

-

As topical as this list feels, it’s actually mostly copied from a short blog post I wrote way back in 2007. See also: Replete from 2009. ↩︎

-

I’ve made the case elsewhere that life is not as short as we think, and we’d be better off to not constantly behave as though it is. ↩︎

-

How much savings do you think you need to retire? I remember having this specific conversation with various colleagues over the years, and even agreeing actual numbers with some. What I have now is so far beyond any numbers I dreamed to estimate then, and yet I’m still filling my days with work. I’m basically a huge disappointment to my former self. ↩︎

Related Essays

Long Enough

How would treating time as a variable that we can influence change the way we behave and the choices we make?

Investment Lessons

Here are four simple but uncommon ideas about investing…

Diworsification

A portfolio approach to early-stage venture investment doesn’t really help and probably hurts.

Show Me the Money

Trying to decide how to fund a startup? It’s important that we ask the right questions.

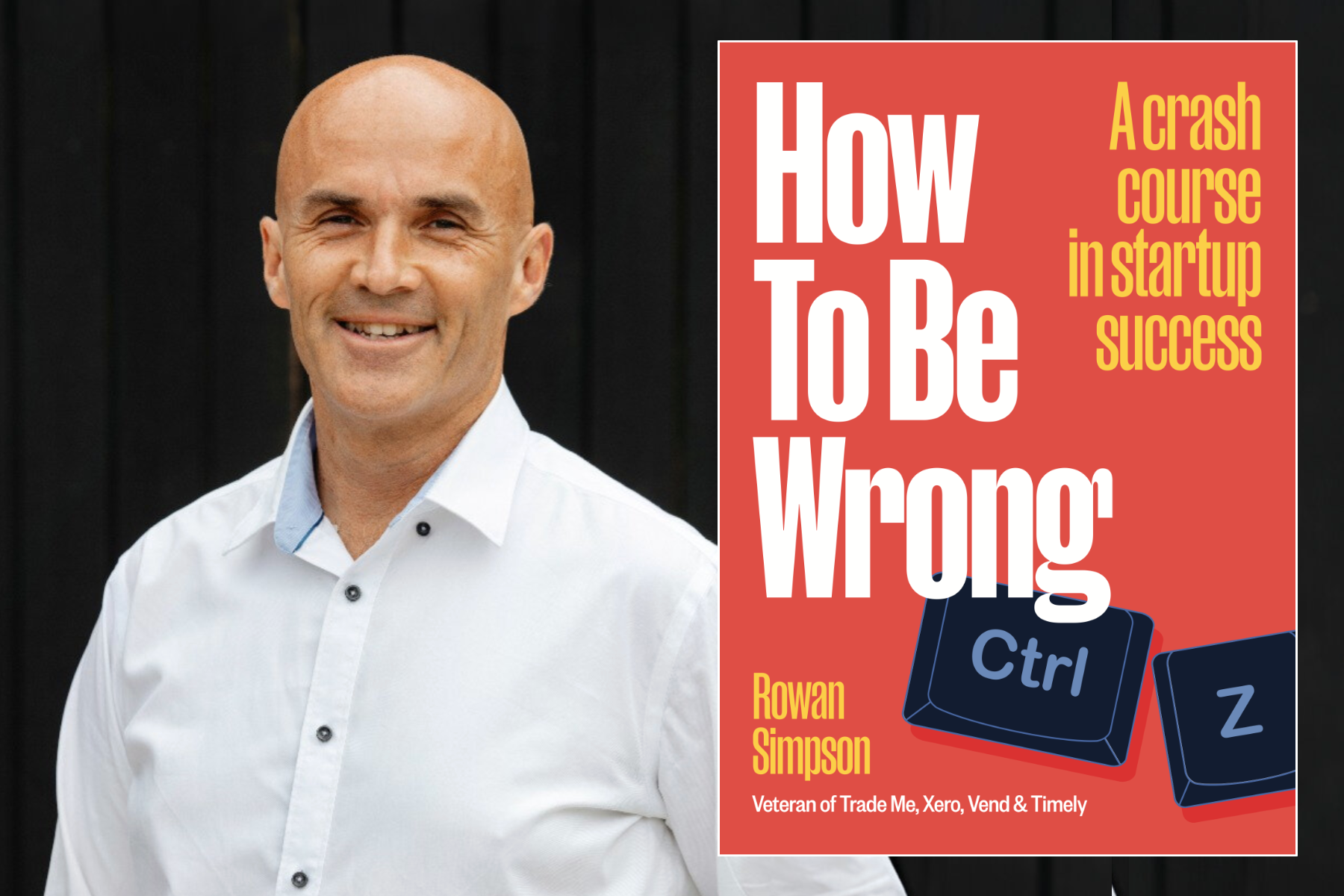

Buy the book