In the long run we win by making something so great that people will pay more for it than it costs us to make.

When constructing a strategy it’s easy to have a lofty end point in mind. It’s better to have a rough map showing how we currently plan to get there. The “currently” is important – goals can be consistent, but plans need to be flexible to change, based on what we learn from each experiment we complete. When we’re planning it’s surprising how often we talk about the destination but not the route. To plot a path, we need to define the intermediate milestones that will show when we’re on track.

If you are a visual person then you might like to represent this as an actual map. Draw a diagram that represents the different elements – current location, route and time estimates as well as destination. If you are a numbers person then you might prefer a spreadsheet that shows the different metrics that will be important and how they interact with each other. If you are a storyteller then you probably prefer a presentation format, where you can share a narrative that will inspire and excite others. I’ve seen all three approaches work with different teams. The important thing is to communicate this plan to everybody who will work together to make it happen: the current team, investors and other stakeholders, and where appropriate even the customers who will ultimately fund it.

Step by step

Perhaps the most famous recent example of a “How we win” plan is the so-called Secret Tesla Motors Master Plan shared by Elon Musk in 2006, long before the company was synonymous with electric vehicles:

- Build a sports car.

- Use that money to build an affordable car.

- Use that money to build an even more affordable car.

- While doing above, also provide zero emission electric power generation options.

This is exactly what Tesla has done.1 Hindsight makes it all look obvious.

Vaughan and I wrote something similar for Vend, on a flight back from San Francisco in 2012. We had spent the previous week unsuccessfully pitching to potential investors. Reflecting on the feedback highlighted the different things we needed to demonstrate in order to raise more capital and ultimately grow the business. We cobbled together a very rough presentation that broke our strategy down into four streams:

- Build a great team.

- Build a great product.

- Develop low-touch sales channels.

- Manage cash.

The first three correspond to the three engines that make up a business. The fourth is the foundation that everything is built on.

Still jet lagged, we presented a version of it to the small team when we arrived back in Auckland. The story was simple: if we do those four things we believe we will win. Later this became a company tradition. As it was repeated over the years it was refined and polished. Some former Venders may fondly remember the versions that Angus (the CFO at the time) would do for everybody as part of the on-boarding of new team members.

Divide and conquer

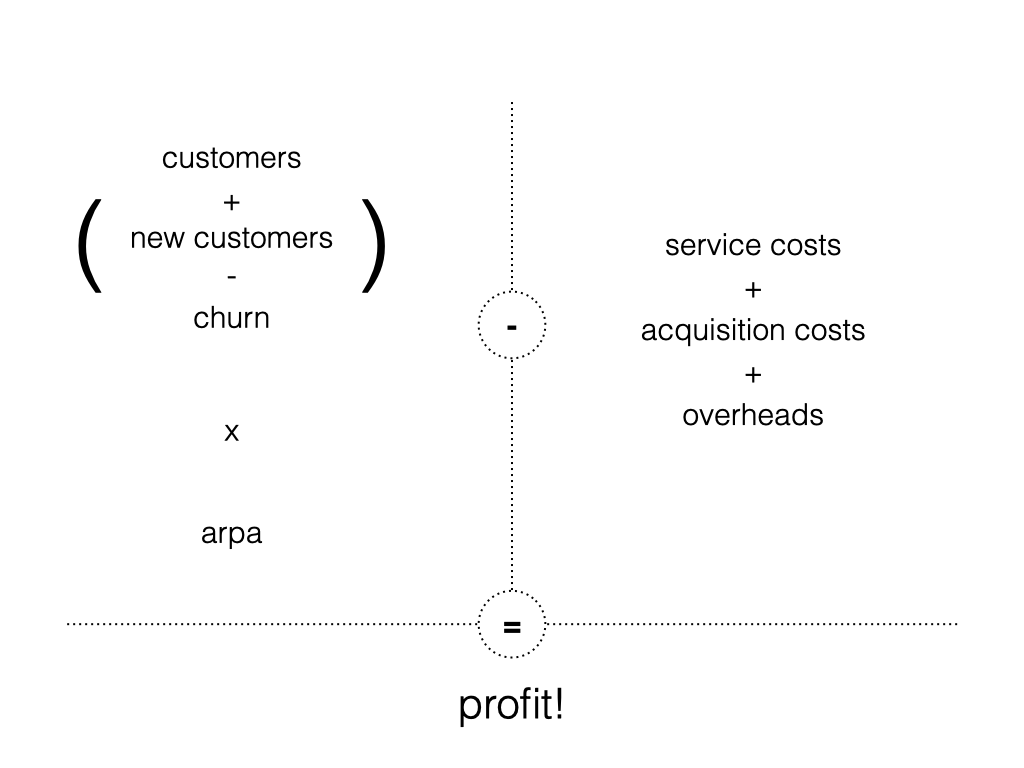

At a Timely full-team meeting in 2017 I presented a similar simple “how we win” model:

It might seem like a lot of maths, but this is actually just the standard business model:

Revenue - Expenses = Profit

With some SaaS specific elements added to provide detail:

Revenue = Customers (Net of Churn) * Average Revenue Per Account

Expenses = Service Costs (CTS or COGS) + Acquisition Costs (CAC) + Overheads

Related: The Size of Your Truck

This breakdown let me ask about each of these elements separately:

- How do we increase the number of new customers?

- How do we increase retention or decrease churn?

- How do we increase the average revenue per account?

- How do we reduce the average amount it costs to service each customer?

- How do we reduce how much it costs to acquire a new customer?

- How do we reduce overheads?

I appreciate this is not an especially exciting list of questions. They are all difficult problems to solve. None of them is glamorous. But these are the things that matter, in the end. This is the hard grind.

This list also highlights the trade-offs. We’re dealing with a number of interconnected dimensions, and it’s impossible to “win” every one. For example, hiring more customer support staff to reduce churn increases the service costs and overheads. We have to pick our battles, and focus on the combinations we believe are most critical or where we think we can influence the outcomes the most. We need to find the things that can be measured which impact that result. Importantly, everybody in the team should see themselves in one of those questions, and be clear how their role within the team contributes to that specific outcome and the overall success.

A metric which became a key part of both Vend and Timely board packs is Tomasz Tunguz’s Cost of a Recurring Gross Profit Dollar (CRGPD).2 This is a great composite metric: it captures lots of different aspects of the SaaS business model in a single number (including the gross margin, acquisition cost and churn). It’s meaningful – if it’s costing more than $1 to gain $1 of recurring gross profit that should immediately raise concern. By tracking the number over time we can quickly see progress – a lower cost is better than a higher cost.

Breathing through eyelids

This divide and conquer approach even works for things completely unrelated to startups.

For example, many years ago I set myself the goal of running a half-marathon in 1 hour 45 mins, which requires an average pace just under 5 mins/km. Understanding that my strength is a high pain tolerance, and realising that whatever happened I was likely to be fading by the end, I decided to go with this race plan:

- 4:46/km to 12km

- 5:15/km to finish

In other words, go out fast and hang on!

The intermediate milestone was 12km in ~57 minutes. I decided not to worry about the second half of the race. I realised that the first half was critical - if I wasn’t on track then I didn’t have a hope. Even though I hadn’t run the full 21km distance in training, I’d done that shorter distance at the required pace, so I knew that was possible. On the day I got there in 56m 16s, which was lucky because my planning hadn’t accounted for the increasing northerly we had to run into on the way back (one of the consistent joys of running in Wellington).

I was delighted to cross the finish line 50 seconds under budget in 1h 44m 10s.

Tolerate

When designing an electrical device one of the important considerations is interference. You may notice the stickers on the bottom of appliances:3

Operation is subject to the following two conditions: (1) This device may not cause harmful interference, and (2) this device must accept any interference received, including interference that may cause undesired operation.

There is a good reason for these rules. There are a limited number of usable frequencies in the spectrum, and there is a lot of overlap between devices. The same 2.4 GHz band that a WiFi router uses might also have to accommodate cordless telephones, wireless baby monitors or gaming controllers.

No device can assume it has the space to itself. It shouldn’t interfere with others, but at the same has to cope with interference caused by others. This is an engineering equivalent of the old Stoic lesson: be tolerant with others and strict with yourself.

The world is full of noise. We have to block that out so it doesn’t become a distraction. But also we need to make sure that we’re not the one making the noise, distracting others. It’s amazing and depressing how often the things that our teams focus on are not correlated at all with how we win. We get distracted by growth rates. We get distracted by the size of our team, or the amount of capital we’ve raised (both vanity metrics). We get distracted by winning awards. We get sucked into ecosystem events and forget that we need to put our own mask on first, before helping others.

Those companies that we read about, after they have achieved great outcomes, are the ones who manage to put these distractions aside and execute a plan that keeps focus on the things that actually matter.

How well does your team understand your plan to win? When was the last time you wrote it down or said it out loud?

-

In 2016 Tesla published an updated version called “Master Plan, Part Deux” (obviously no longer secret). ↩︎

-

A New Way to Calculate a SaaS Company’s Efficiency by Tomas Tunguz, 1 December 2018. ↩︎

Related Essays

The Size of Your Truck

As we grow, take the time to understand unit economics.

M3: The Metrics Maturity Model

Use these simple steps to improve how we measure and report our progress.

Machines & Phases

There are so many different ways to measure a startup. It’s easy to drown in metrics. How do we separate the signal from the noise?

Discomfort

How can understanding our relationship with pain help us conquer challenges?

Startup Theatre

To encourage more people to work on startups, we often try to make them fun. How does that hurt?

Buy the book