Here are four simple but uncommon ideas about investing…

1. We can’t invest in nothing

Especially when there is a lot of volatility and uncertainty it’s tempting to think that we can opt out and not invest at all.

But, whether we like it or not, everything we have is invested in something. Investing in nothing is not as easy as it looks.1 We can’t choose not to choose.

Perhaps we prefer to keep our cash under the mattress. In that case we are investing in the specific currency we’ve selected and we are betting against inflation.

Perhaps we put our money in the bank or on term deposit. In that case we are investing in the institution that holds that cash for us. Of course, they almost certainly don’t actually “hold” it as cash – so, it’s worth considering what they are doing with our money in order to be able to pay us interest and still have a profit left over for themselves. Those folks who invested in finance companies prior to the GFC in 2008 learned the hard way these sort of investments are not zero risk.

Perhaps we invest in the stock market. In that case the choice is a bit more obvious. Hopefully the particular company we picked does well, so the share price goes up. Or, maybe the company will do well, but not as well as others were expecting, so the share price goes down (remember, on the public markets, a share price is just a measurement of current market expectations).

Perhaps we prefer to hedge our bets a little by investing in an index fund. However, an index is just a collection of individual companies and this same logic applies to each of them and therefore to all of them together. The reason why investing in an index is considered lower risk is because the returns will be average - i.e. gains at one company will offset losses at another. But the average can still be negative.

Perhaps we like to own real estate. In that case we’re investing in a local property market. If we have a mortgage we are borrowing (and paying interest on that loan) in order to be able to invest more than we would otherwise be able to afford. It’s interesting how much people are willing to borrow to invest in property when they would be very unlikely to do that for any of the other investment options listed above. Presumably they believe the risk is lower and that the gains will still be positive even after all of those expenses are included2, and so choose to leverage that investment.

Perhaps we have invested in our own small business. Actually, those who do this usually invest in multiple different ways - firstly by putting in the capital to get the business off the ground, and then by paying themselves less than they could earn elsewhere. These are just slightly longer term investments, in the hope that the business will grow and generate a return. When we look at it this way, I wonder how many small businesses perform better than the equivalent amount of cash in the bank, when all things are considered?

Perhaps we prefer to spend than to save. At least by investing in expensive toys today we will have less of a problem deciding what to invest in down the track!

Even if we choose to give our money away, we’re effectively making an investment in a specific charity or non-profit to do something useful with that money. Or not, as the case may be.

Perhaps we just spread our bets, and do some of all of these things?

Still, every dollar we have is invested in something.

2. There are no shortcuts

There is no such thing as “free”.

To say that something is free is just another way of saying that it’s paid for by somebody else, paid for at some other time, or paid for in some other way.

This is true of free education, free healthcare and free shipping.

Rather than constantly looking for ways to make something cheaper by offloading or deferring costs, it’s more useful to understand that the things we value the most are expensive, and be willing to pay for them (sometimes directly, but often indirectly).

I recall this wise observation, from a conversation I had with an NGO worker in Africa many years ago, where he was describing the pressure he was under to provide goods and services for free, both from the poor people he was trying to help and the rich donors who enabled him to be there:

When you ask me to give something to you for free, you are giving me all the power – to choose who gets what and when. And, to be honest, I don’t believe you really want to give me that power.

When you pay me you create an expectation that I will deliver value for money. I may or may not, and that is the risk you take, but the expectation exists nonetheless.

It’s worth thinking about what we’re giving up next time we appear to get something for nothing. Often, if we’re not paying for the product we are the product.

The secret to sustainable investment returns isn’t finding the previously undiscovered shortcut or the bigger fool, it’s just being willing to do the work.

3. It’s okay if other people win

It’s tempting to think that the goal of investing is to “get ahead”.

In New Zealand the most popular way that we’re advised to get ahead is to be on the “property ladder”. Even that metaphor is interesting to me. The implication is there are well defined levels, and the goal is to climb up through those over time.

Research would suggest we are quite motivated by relative results. For example, when we control for other variables, how our income compares to our peers influences our overall happiness more than the absolute amount of income we receive.

But investing is not a zero-sum game. We don’t “win” at somebody else’s expense. Indeed, the most successful investments generally produce a great return for lots of people. The more the better!

It’s okay if somebody else makes an investment that goes well. That doesn’t mean there is somehow less left in the pot for us. We don’t need to worry about what other people are investing in or what returns they are getting. We just need to worry about the things we are investing in, and whether the returns we’re getting are good enough.

It’s dangerous to predict that somebody else is making a bad investment before that is obvious. If we are correct then we look mean. If we are wrong then we look silly. We lose either way.

Anyway, in the best case, we can only tell how good their outcome is from the outside.

This is especially true for startups. It’s amazing how often what is presented as a great exit was actually a lot of drama for those investors who were directly involved. And, depressingly, the true stories are often not what get shared and amplified.

Related: The Plunge

We should try to avoid comparing how we feel on the inside with how other people look on the outside.

We need make sure that the fear-of-missing-out doesn’t cloud our judgement.

The challenge isn’t to invest in everything that might be good.

I’ve seen some of the most successful early-stage investors pile into an investment without giving it the necessary attention, when they felt like the might be missing out on something.3 I’ve done that myself.

In those situations it’s easy for everybody to assume that somebody else has done the work to validate the opportunity. But, far more often, it means that nobody has done the work.

And that’s a terrible way to make investment decisions.

4. Everything is just a row in a database

It’s easy to get a bit myopic about a particular asset class.

We are all biased towards the particular things that we like to invest in.

This is true for those who invest in startups and those who invest in real estate. It’s especially true for those who invest in crypto.4 It’s even true of those who advise a balanced investment approach.

It’s useful to step back and realise that everything is just a row in a database.

Our bank account balances, share registers, property titles, and bitcoin wallets.

None of these things are, by themselves, intrinsically or inherently valuable.

Once we have that mindset, then we can try and think a bit more clearly about what makes these things valuable to us now, and what will mean they might still be valuable (or hopefully more valuable) to us in the future.

-

Seinfeld: “What have I been doing? Nothing!”

↩︎

-

When we calculate the returns on property investments it’s important we include interest costs, but also insurance, rates, maintenance and the opportunity cost of capital. Many property investors are also landlords, so should also factor in the cost of their time. On a purely mathematical basis perhaps investing in property isn’t a rational choice, once all expenses are considered, but this was still the first thing I did when I had the opportunity.

One of the things that complicates this is that a house can be an investment, but is also a place to live. When we treat property as a retirement savings scheme, as many people in New Zealand do, it’s useful to remember that you can’t eat your house. ↩︎

-

For example, this partly explains the increasing popularity of convertible notes in early stage investing - these offer a “discount” on a future valuation, which makes investors feel like they are “getting ahead” of those imaginary others who might invest later. ↩︎

-

Likewise, it’s also true for those people who hang out at the TAB all day or keep going back to the casino. ↩︎

Related Essays

The Plunge

Why do the most interesting bits of startup stories always get airbrushed out?

Diworsification

A portfolio approach to early-stage venture investment doesn’t really help and probably hurts.

Enough

Those without naturally want more. Meanwhile, those who have a lot want less. How do we all decide how much is enough?

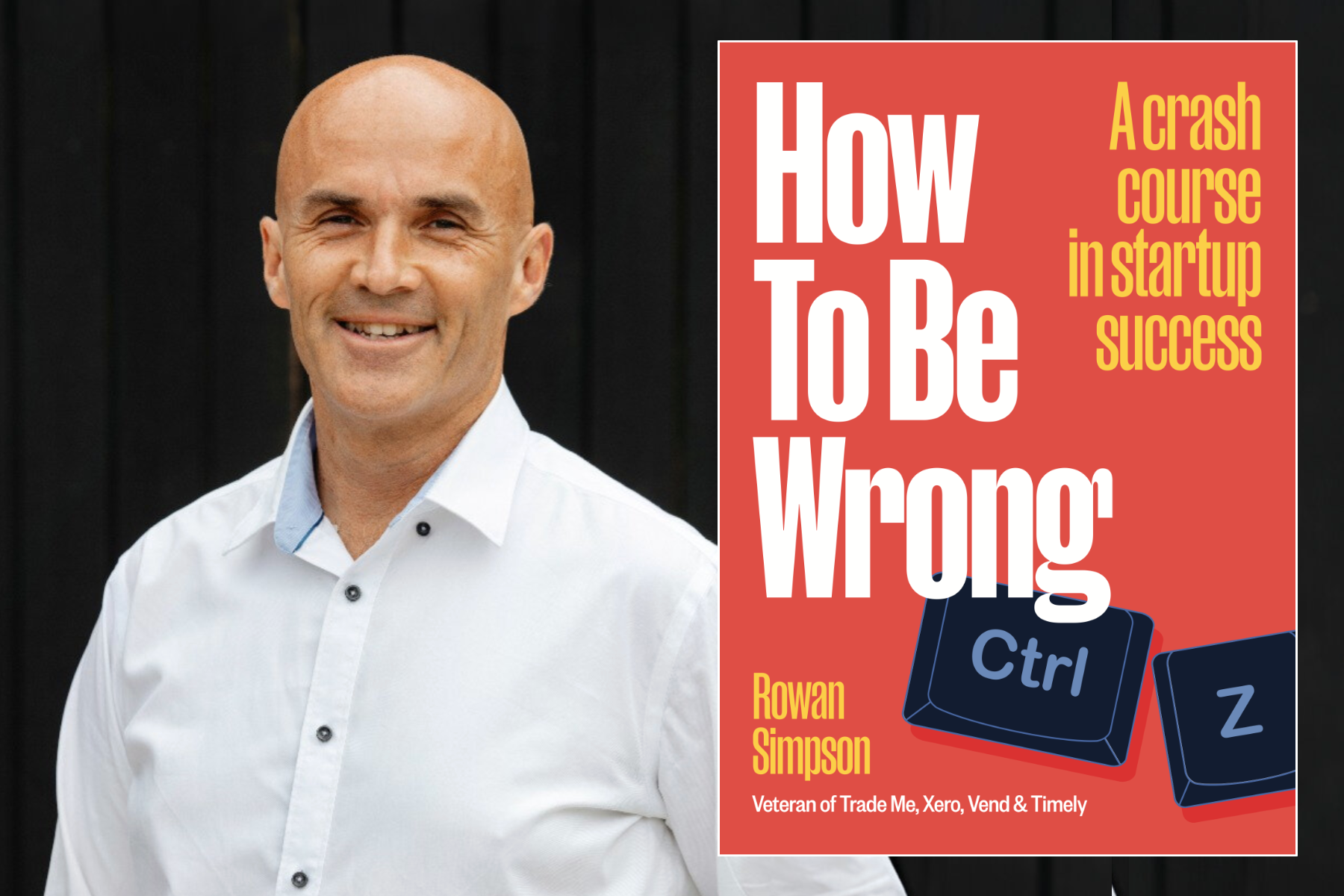

Buy the book