Until you make the unconscious conscious,

it will direct your life and you will call it fate.

How much of success is actually just good luck?

Dealing with the whims of fortune is part of being human. Sometimes it helps us, sometimes it hurts us. People who have been on the receiving end like to say:

The harder I worked the luckier I got.

No doubt, working hard is a prerequisite, but I’ve also worked hard on ventures which failed. I prefer to look at it differently. Rather than belittling the role that luck played, we should be more specific. There are many ways we can create “luck”, or at least put ourselves in positions that increase our chances of success.

When-Luck

Timing is everything.

Trade Me is a great example of this. The site launched in 1999, the same year as the very first ADSL internet connection in New Zealand, and a year before the Southern Cross Cable was commissioned. Many people were connecting to the internet for the very first time, and were hungry for something to do with it.

By 2006, when we sold to Fairfax, about 70% of New Zealanders were online and about half of those were high-speed broadband connections. That trend gave us a fast-growing group of potential customers. It also created serious challenges – we needed to ensure we didn’t push beyond the capability of the browsers and internet connections that most people were using, and we had to teach people the basics of how to protect themselves online. While both of those things felt like work at the time, they made us stronger.

Many successful startup ideas are failed startup ideas from an earlier era. For example, the CEO of Andersen Consulting, where I worked until 1999, was George Shaheen. He left the company about the same time as me, apparently one year short of qualifying for a lucrative retirement package, to move to Silicon Valley as the founding CEO at Webvan. That startup became one of the high-profile failures from the initial dot-com bubble – they raised US$375 million in a public float and were at one point valued at nearly US$9 billion, but by 2001 were out of business. Online groceries were an expensive mistake in 1999, but an essential service in 2020.

It’s not enough to have an innovative idea, we also need to execute. But it’s much easier to execute if we’re selling something that people are ready to buy.

To create what I call When-Luck we need to look for the waves that are coming next, and paddle to position ourselves so we are there ready to capitalise on them when they break.

Where-Luck

We shape our environment, but mostly we are shaped by our environment. For example, it’s not an accident that Xero was started in Wellington. It was, at the time at least, a great melting pot of people with recent relevant startup experience looking for the next interesting thing to work on, including some of us with capital to invest from recent exits. It’s a small city, physically constrained by the harbour and hills. It often feels like everybody there knows each other. There are lots of opportunities to bump into other interesting people. It’s also famous for terrible weather – the wind and rain that hit you sideways certainly create plenty of incentive to be indoors and working hard.1

That might feel like a unique set of circumstances. But actually every place has a competitive advantage. We just need to find it, describe it, appreciate it and make the most of it.

It’s not just cities. We can also apply this idea to our whole country. With the benefit of hindsight New Zealand was the perfect place to test Xero’s go-to-market strategy (using accountants as a channel to small business customers) that would later work successfully in much larger markets in Australia and the UK. Big enough to highlight the lessons but not so big that the potential got stamped out before it could gather momentum.

We should reframe New Zealand’s geographic isolation as a feature rather than a bug. We’re not a long way from anywhere, in the middle of nowhere, unless we believe right here isn’t somewhere.

Related: Small Island?

But we need to be aware of the downsides too: When I first started travelling internationally in the late 1990s I discovered that EFT-POS was something we took for granted in New Zealand but which was uncommon elsewhere. We were early adopters. However as a result we were slow to switch to the next generation contactless payment technology (ironically it was the COVID-19 lockdown here which was the tipping point for things like contactless payments to finally become much more widely supported). Our payment systems were like the flightless birds that evolved in Aotearoa due to the long absence of predators.

To create what I call Where-Luck we need to understand and leverage the advantages we get from our environment. The slightly less comfortable way of saying this is: if our current environment isn’t a good match for what we’re working on, we probably need to move.

Who-Luck

The cliché is: it’s not what you know but who you know.

We can hear that and complain that we don’t know the right people. Or we can realise we all know people. Remember, we are the average of the people we spend the most time with. The question is does our specific group lift us up or drag us down?

Team culture is a huge and under-appreciated aspect of all successful startups. This is why second-time founders sometimes struggle to repeat their success. It’s a long, hard job to build an impressive team with a strong culture. Those are both rare and fragile things. It’s daunting to go back to the beginning and start again.

Every team is the average of the people in it. We end up spending a large amount of time with our colleagues, and they either lift us up or drag us down. But there is an even larger group of people we should have in mind, too. I’ve attended and even spoken at many startup events over the years. The irony isn’t lost on me when I say “prioritise talking to customers” to a room full of people who are prioritising listening to me rather than talking to their customers.

To create what I call Who-Luck we need to carefully select the people we choose to work with and sell to.

What-Luck

What unique combination of skills do we have?

Steve Jobs once described Apple as a company that exists at the intersection of technology and the liberal arts.2 In his mind it was the combination of these two things that made it great. As he explained:

Creativity is just connecting things. When you ask creative people how they did something, they feel a little guilty because they didn’t really do it, they just saw something. It seemed obvious to them after a while. That’s because they were able to connect experiences they’ve had and synthesize new things. And the reason they were able to do that was that they’ve had more experiences or they have thought more about their experiences than other people. Unfortunately, that’s too rare a commodity. A lot of people in our industry haven’t had very diverse experiences. So they don’t have enough dots to connect, and they end up with very linear solutions without a broad perspective on the problem. The broader one’s understanding of the human experience, the better design we will have.

— The Next Insanely Great Thing, Wired, February, 1996

This is a powerful idea that we can use to select and shape the things we work on. But it requires two uncommon adjustments. First we need to accept that being excellent at just one thing is often insufficient. Then we need to think harder about how the skills we have can be combined. This is true for individuals. But it’s especially true for teams. When everybody we’re working with looks the same and thinks the same, there is no intersection. But when we have different people bringing different skills and experience to the group, the whole can be much greater than the sum of the parts.

To create what I call What-Luck we need to understand our unique collection of skills, both individually and collectively, then explore the ways they complement each other and combine to create something new.

Why-Luck

These different types of luck all reinforce each other. We can create another kind of luck, what I call Why-Luck, right at the very beginning of a venture by clearly articulating our values.

Brianne West, the founder of the Ethique health and beauty brand, has a nice way of describing this. She says she is often asked: “How did you grow so fast without compromising your values?” That is a confusing question because, rather than holding them back, their values have been a key to their success. As she explained in a post on Instagram:

Without a solid brand that believed in making the world a better place, Ethique was just another hair care brand in an oversaturated industry. Our values drew people to us, engendered die hard loyalty, and brought people on the journey with us celebrating the highs and helping us through the lows.

The more ambitious and meaningful the mission, the easier it will be to attract others who resonate with it, and will want to join the team. When we create meaningful jobs and a team environment that supports and encourages and challenges people to be better, we attract people who lift the performance of the team. This in turn increases our Who-Luck, and in some cases mitigates bad Where-Luck.

Pure-Luck

None of this is to say that pure chance won’t sometimes play a role – at best wonderful, at worst horrific. In any venture there will inevitably be critical moments when we desperately need to roll a double-six or we’re done. But those are rare. When people talk about “making your own luck”, what that really means is consciously putting yourself in situations where you have the chance to be lucky. That’s how it worked for all of the “lucky” people you envy and admire.

My dad used to tell a joke about a down-on-his-luck man who would pray every night:

Please, Lord, let me win the lottery this weekend.

But his prayers were never answered. He repeated that for years and years, without ever winning, until one night, there was a boom of thunder and God replied, slightly exasperated:

Listen, mate, I’d like to help, but you need to buy a ticket!

(To be clear, relying on God and Lotto is not a strategy I recommend.)

-

For a sardonically funny visualisation of this effect, see Adam Shand’s Realistic Wellington Calendar. ↩︎

-

Steve Jobs: Technology & Liberal Arts, YouTube. ↩︎

Related Essays

People, People, People

Ask the best startups what’s holding them back and they all point to the challenges of finding and keeping great people.

Inconvenient Values

Why is it so hard to articulate and document shared team values?

Head first, then feet, then heart

What could we be great at? What are we willing to take responsibility for? Combine those two things and maybe we can change the world!

Monochrome

What can rugby teams and rowing squads teach us about building and managing diverse teams?

Scar Tissue

Working on a startup is much more like racing a BMX bike than riding a roller coaster.

Flailing

Here is some unusual advice for people working on a startup, or thinking about it: swim.

Most People

To be considered successful we just have to do those things that most people don’t.

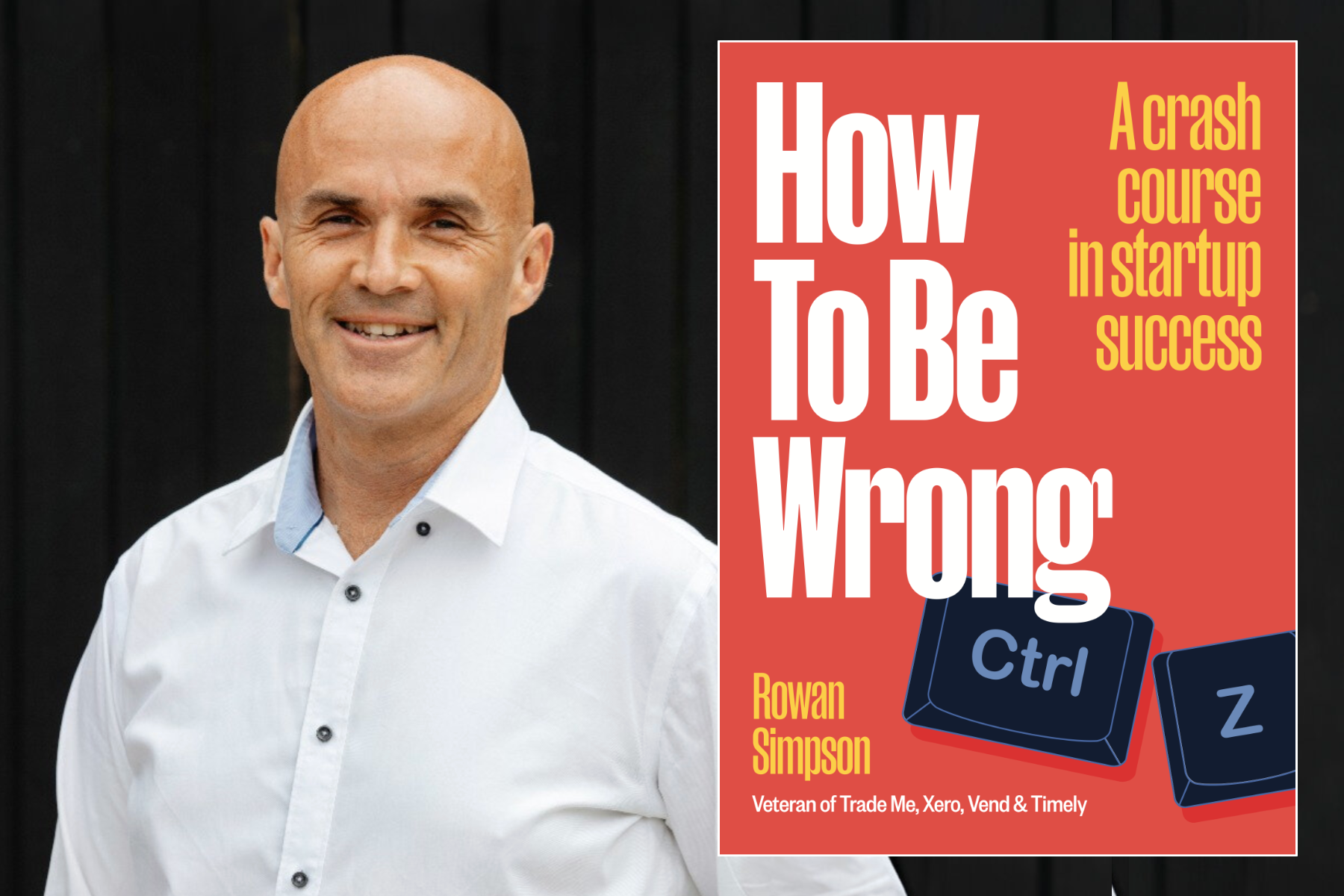

Buy the book