Once upon a time…

Here is the popular mythology about how a new technology business becomes a success:

Our hero, a lone genius, slightly lacking in social skills, one day comes up with an amazing new idea for a website. They lock themselves away in their bedroom and stay up all night typing furiously. They launch the next morning and are immediately inundated with customers. Shortly after that, they convince a slumbering corporate into buying the company for squillions and then retire to spend the rest of their life happily sipping mojitos on the beach of a remote tropical island.

This fairytale narrative is pretty harmless, I suppose.

But for anybody actually working on a startup, or considering it, it’s a real distraction because many of the things that people think they know about what it takes to create and grow a successful business are wrong.

The path to success is unlikely to be the exact same path taken by somebody else who was successful.

Besides, those who have been successful find it much more difficult to pinpoint the reasons for their success than we might imagine. The decisions they made were typically a mixture of strategic foresight paired at just the right time and place with good execution, ultimately inconsequential mis-steps and lucky stumblings. It’s only much later that they get to decide which of these were which.

On the other hand, we don’t often hear from the founders who tried something and failed, despite the fact that the lessons they uncovered in the process of not making it are likely much more relevant than the post-rationalisations of the lucky winners.

So, what should we be paying attention to as we try to get our new venture off the ground?

Let’s try to break down this mythology and explain some of the counter-intuitive lessons, using examples from the ventures I’ve been fortunate enough to work on.

🎷 One Man Band

Cofounders are for a startup what location is for real estate. You can change anything about a house except where it is. In a startup you can change your idea easily, but changing your cofounders is hard.

Any successful technology company requires a mixture of different skills (in no particular order of importance):

- Software development

- Design and user experience

- Operations

- Marketing

- Sales and business development

- Strategy

- Finance and administration

- Customer support

Even within each of these areas there are conflicting demands.

A good software development team needs a combination of people whose primary stengths are heads-up (thinking about people and how they use the software) and heads-down (thinking about the machine and how to make everything run as fast and efficiently as possible).

Smart strategy requires a very rare mix of faith-based and fact-based thinking.

Related: Continuums

All of this means that it’s extremely unlikely that we can do everything ourselves. Instead, we need to surround ourselves with people who can cover the areas where we’re not strong—and ideally, in the beginning, generalists who can cover more than one area: somebody who can code and help with sales and support.

Here is a good rule of thumb: if we can’t convince at least one other person to work with us, it’s likely that your idea is not great. A business with a solo founder is like an operating system that can only run one application at a time: they can sell to customers, or do support, or build product, or fix bugs, or hire, or manage, or fundraise … but only one at a time, and with horrendous context-switching costs.1

More than that, you need a mix of perspectives. You can avoid many common and obvious mistakes and perform better as a team by including people with diverse backgrounds and experience, rather than hiring a bunch of people who all think, act and look the same way you do.

Related: Monochrome

As we grow, the team culture is established quickly, so those early hires are critical. It’s vital to think very early on about what values we share as a team. These shouldn’t just be platitudes to be stuck up on the wall, because they will inform the way decisions are made, including how we will grow the team and product, for better or worse, and even how we will respond when the pressure comes on down the track.

Related: Inconvenient Values

It’s also important that at least one person on the team is a technical person. If this seems unfair to the majority of people who can’t code, consider this: what is the most successful technology company you can think of that didn’t have a co-founder or early employee who was a developer?

Never in modern history has it been so easy to create something from scratch, with little or no capital and a marketing model that is limited only by your imagination.

Most of the people who contact me with an idea for a new venture are not technical people, and so have no idea what is really involved in building software. And yet most developers seem to prefer to be employees, not realising that the skills they have mean they are effectively sitting on a goldmine. Why is that?

My guess is that most people want to stick to what they are good at rather than extend themselves into areas where they are likely to struggle, at least initially, such as sales and support.

Another important ingredient is choosing the right investors. Perhaps we have enough money of our own that we don’t need investors, or perhaps we can get by with funding provided by people who share our surname. But probably not.

The good news for founders is that these days it seems everybody with some spare cash wants to call themselves an angel investor and fund the next big winner.

The surge in popularity for early-stage investing over recent years has seen investors group together into networks and clubs. Unfortunately this sort of structure often seems to select the worst ventures, because in a club everybody tends to rely on somebody else to do the work to identify and validate good opportunities, meaning that actually nobody does.

Investors are the tender to a new venture, not the engine.

We should seek out investors who take a founder-centric approach. My advice is to choose based on the contribution they can make. In the long run that is likely to be much more meaningful than the amount of money they can provide in the short term. The best way to judge this potential is to look at the trail they have left from previous ventures. It’s worth trying to understand why potential investors care about our success, or even what success is from their perspective.

Whether the gap is a co-founder to share our vision or an investor to provide the fuel and push us along, we need to choose carefully. We will soon discover the true character of these people, when the going inevitably gets tough.

🛁 Eureka

If you're not embarrassed by the first version of your product, you've launched too late.

Most founders are very focused on their idea. But when you look at ventures that have actually been successful, they often look completely different from what they were first intended to be. In fact, there are lots of familiar examples where the idea that eventually worked is so different as to be unrecognisable (PayPal, Instagram, Twitter, Slack, and many others).

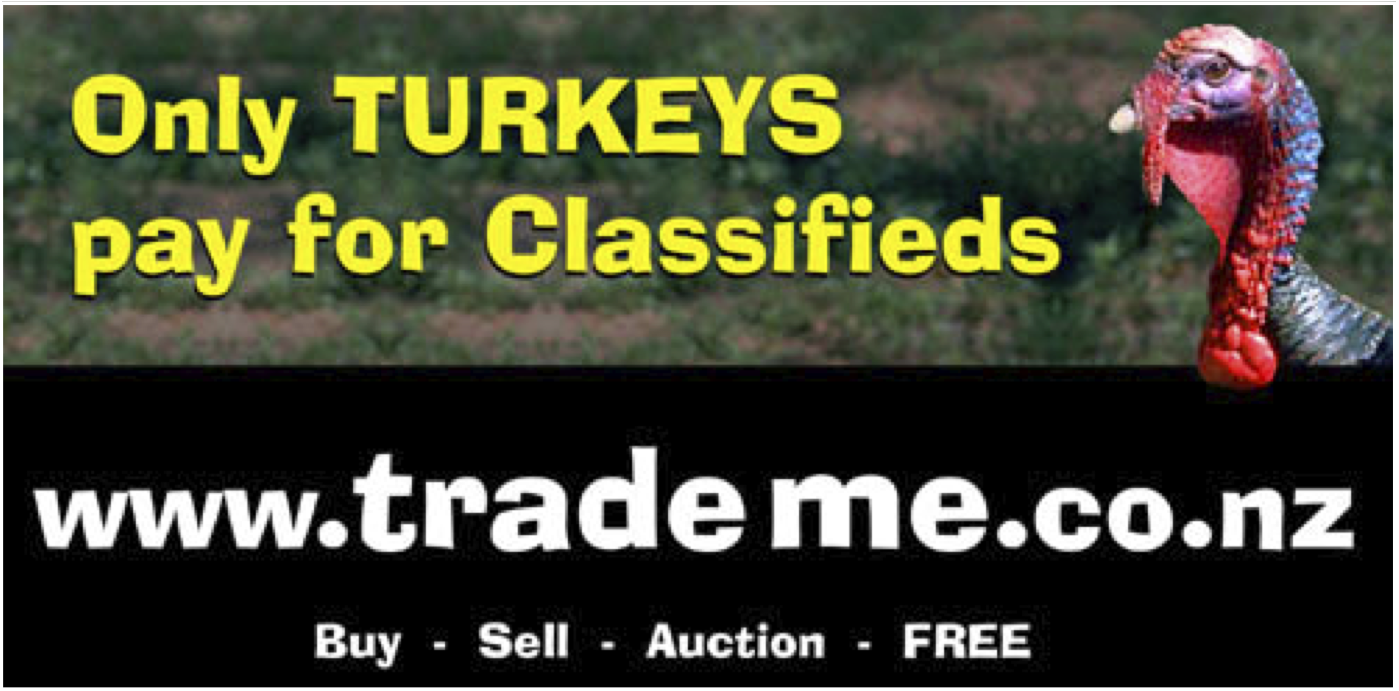

In 2000, when Trade Me was still free, the tagline we used on the first billboards was: “Only turkeys pay for classifieds”.

(The idea that Trade Me didn’t waste/spend any money on traditional marketing like billboards is another myth, unfortunately. We were lucky that we didn’t have much money at that time, or we might well have wasted more of it on stuff like this!)

Initially, we thought free online classifieds would create a large audience, and we could fund the business by selling advertising. It turns out we were the turkeys for thinking this business model was the best option.

This is what the Trade Me home page looked like when I first started working on the site:

We thought it was great—including the Wingdings inspired logo. Now it’s a little embarrassing. But that’s the point …

The only way we learn which parts we need to be embarrassed about later is by launching and listening carefully to the feedback we get.

We need to hear to what people say, but most of all we need to pay close attention to what they actually do. An empirical approach like this makes us humble. We quickly learn what little things we got right and what big things we got wrong.

So, don’t try to partially complete the whole product: complete a part of the product (preferably the part that will demonstrate value to paying customers). Then extrapolate from there based on how people actually use it. It’s nearly always better to implement a smaller number of features really well than trying to do everything averagely.

If we get this right over time then we too can look back and retrospectively invent a story about the mythical magical moment when the idea popped into our head, perfect and fully formed.

🥼 Inventor in a Shed

Often the people who invent something and the people who work out what that thing is for are different people.

A natural instinct of an inventor is to hide away from prying eyes, waiting for the opportunity to reveal the completed invention to a wowed audience. The danger with this approach is avoiding the temptation to constantly add just one more feature before telling anybody about it.

It’s easy to spot an inventor, as opposed to an entrepreneur. The inventor will ask us to sign a non-disclosure agreement before they are prepared to tell us anything, whereas the entrepreneur will happily talk to anybody who will listen.

If there is information that we’re reluctant to reveal because it could jeopardise our venture if a competitor got hold of it, that is a good indicator that our idea is not very good. Likewise if we think someone could take our idea and execute it better than us, even with our head start.

So we shouldn’t lock ourselves away in a shed. We should talk to everyone we can. Perhaps one of them will suggest an improvement we haven’t thought of or, even better, offer to work on it with us - both great outcomes.

That is easy advice to give, but much harder to do in practice. It takes a lot of courage to tell others about our ideas, because chances are they won’t be anywhere near as excited about them as we are.

Inventors have a bias towards creating something innovative and new. But to be successful, our idea doesn’t necessarily need to be original. Amazon wasn’t the first online store, Facebook wasn’t the first social network and Google certainly wasn’t the first search engine, but they have all done okay.

(On the other hand, all three, while not original, had something that was remarkable: Amazon had an extremely deep catalogue and discount pricing, at least initially; Facebook encouraged people to use their real names and was limited to college students only, allowing users to tap into their existing networks; and Google had PageRank. And because they were remarkable, people told their friends.)

There is even a school of thought amongst some investors that says the idea itself is irrelevant. It doesn’t really matter how original your widget is, instead impress with your unit economics and business model and repeatable plans for selling. That last bit is what most frequently seems to be really hard.

Inventing something genuinely new is great, but working out what something is for is where things really get interesting. To create value we need to execute a good idea.

We don’t typically win by getting one big thing right, we win by getting thousands of little things right. And to do that, you need to be willing to get lots of things wrong.

🧑🚒 The Firehose

Lots of effort is wasted by startups who are worried about being inundated at launch. Unfortunately, despite all the work done in preparation, the anticipated deluge of customers rarely eventuates.

Trade Me, like most of the overnight successes you read about in the media, actually took about seven years from launch to acquisition. These days Trade Me is a juggernaut. But the numbers in the beginning were much less impressive. It took four and a half months to get to 1,000 registered members, even though it was completely free at the time. The first 10,000 members took over a year.

Xero remarkably listed on the NZX in 2007 with only 100 paying customers, and those of us working there at the time accounted for a good portion of those. Now that it has millions of customers it’s easy to assume the company was always going to be successful. But, actually those early days were much more of a slog - even a full year after the listing there were only 1,408 paying customers, and it took more than five years to convert the first 100,000.

When we first start out, and actually for quite a while afterwards, it’s hard to differentiate between a hockey stick growth curve and a flat line. To make this even more confusing, the customers we attract at the outset are probably not even representative of the audience we’ll eventually chase.

In the beginning, the biggest category on Trade Me was computer parts. Later it was womenswear. There isn’t a lot of overlap in those categories. Likewise for Xero, many of the early customers were independent contractors, who didn’t need the more complex accounting features we were still busy building, and so were happy to use it even though the product was incomplete.

When we’re just getting started, we need different strategies. We need to make sure that we are selling to those people who are ready to buy, and there may not be a lot of them.

At Trade Me we were inspired by the Team New Zealand mantra, which helped them to focus on the critical things:

Does it make the boat go faster?

I still think that’s great advice for companies that are underway, but before we can worry about that we need momentum.

You cannot steer a boat that’s not moving.2

I don’t have any magic bullets to help generate momentum. In fact, my track record of starting something from scratch is probably not much better than chance. But, here are a couple of things I’ve observed that I think can increase the odds:

1. Have a number to obsess about.

Work out what one thing we can focus on that will create a positive feedback loop and drive the success of our business model.

At Trade Me, in the early days, this was the number of unique sellers using the site. We correctly guessed that if we could increase that then it would create a positive feedback loop: more sellers would mean more stuff for sale, more bids, more successful auctions, more feedback placed and most importantly more people telling their friends that they’d be crazy not to list their stuff for sale too.

At Xero, we focussed on the number of bank accounts that were connected to automated bank feeds, because we could see that the user experience was so much more sticky for those customers.

Once we’re paying attention to something specific, it will hopefully highlight what is currently constraining our progress in that area and help identify the things we can do to move that number in the right direction.

2. Do something different.

People only tell their friends about things that are remarkable (or remarkably terrible!) Unless there is something genuinely different about our idea it probably won’t be news, so we’ll need to find some other way to spread the word.

We were fortunate at Trade Me to have an idea that was inherently viral: once a new user sold some stuff that they assumed was worthless, they couldn’t help but tell others about it.

It wasn’t so obvious at Xero, but in time the focus on accountants and book-keepers, both in terms of product and in terms of sales and marketing, has proven to be an amazing way to spread the word and get in front of millions of potential small business customers.

Our idea may or may not be inherently viral like Trade Me, or be blessed with a lucrative distribution channel like Xero, and it makes a big difference — alternatives will almost certainly be more expensive.

Expand your operations once you have operations

— Jason Fried, 37signals

It’s very tempting, especially for technical people, to focus too soon on designing for scale. In practice it nearly always ends up looking like premature optimisation. We probably have more time to worry about this than we think, and adjusting for it, if and when it arrives, is probably not as difficult as we might imagine. At that point we will be starting not with a blank sheet but with all of the information we have gathered and lessons learned about what works and doesn’t work in our particular circumstances, which bits of your application are actually used a lot and where the biggest bottlenecks are.

Before we have customers there are definitely more important things to be working on… like getting customers.

No matter how well we execute, it’s almost certainly going to take longer than we think before it becomes a success. But, that’s actually a good thing: creating something really great is going to take time and if we realised up-front how long it will likely take we might not bother to start at all.

🤑 Pinch Me!

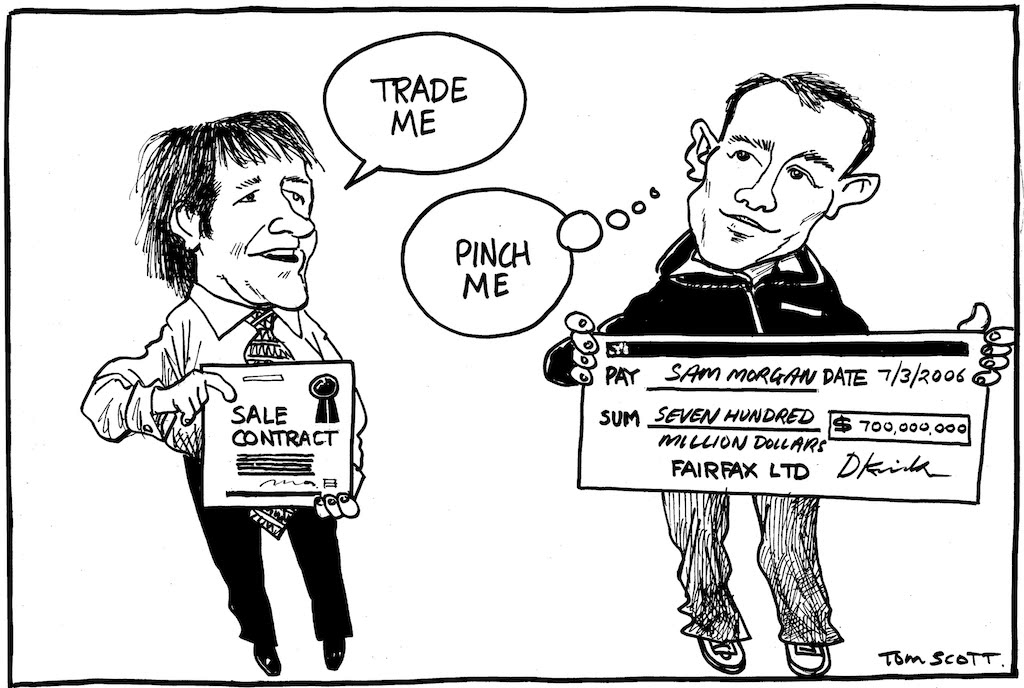

In 2006 Trade Me was sold to Fairfax for $750 million. At the time, some people thought that Sam Morgan had somehow tricked David Kirk into adding an extra zero to the price tag.

Tom Scott in the Dominion - March 8, 2006

In 2007, we floated Xero at a price which valued the business at $55m. There were some people during the IPO process who joked that it was the first company named after its revenues.3

Why was Fairfax prepared to pay so much for a website? And what made Xero worth that much, despite having so few customers? In simple terms, these prices were a multiple of the earnings and the trajectory the businesses were on. What many people failed to appreciate was the amount of free cash flow that a business like Trade Me generated, and how much global potential there was for Xero if it could get established. In both cases the prices then seem cheap compared to the value that was eventually created.

So, what do we need to do to attract the interest of an investor or acquirer for our venture?

We can start with two basic motivating emotions:

- Fear

- Greed

In other words, we need to have new (and often more importantly) growing revenues, or we need to be threatening existing revenues.

The good news for founders is that the strategy we should follow in either case is the same: build momentum, prove we can sell repeatedly and create a business that makes money. If we do that, we will have no problem selling the company or attracting investment if and when we decide that we want to.

And in the meantime, we shouldn’t get too far ahead of ourselves. There are two possible reasons why people are not prepared to pay you what you think you’re worth: 4

- People don’t know what you’re worth; or

- You’re not currently worth as much as you believe.

So, get going and build something that makes it more obvious that we’re the next big thing and at the same time lower our valuation expectations and see if that makes a difference.

In 1999 Trade Me took on $100,000 of investment, and in return the investors got 50% of the company. In the end it was a good deal for both sides, and for me too as Sam used some of that money to start to build a team.

These days most of the people I talk to think just their idea alone is already worth millions of dollars. The vast majority have no revenues to speak of, and no idea what it will really cost to get to a point where they do, and therefore no basis at all to put this sort of valuation on the business. Worse, when we really dig into it, most know that what they have isn’t really worth that much yet, but they have convinced themselves (or been convinced by their advisors) that they can somehow trick somebody into investing anyway.

This is crazy. We should choose the investors we want to work with, be honest with them (for example if somebody asks for your long-term revenue projections, tell them we don’t and can’t possibly know yet), give them enough equity to make it material for them and ask them to help us push it along however they can. For both investors and founders, success comes from creating a great business—not by screwing every last cent out of a funding round.

Whatever we do, don’t be a want-repreneur, sitting around waiting for investment before we even get started. Chasing money from outsiders before we have a working product is probably not a good use of our time anyway: the investment terms we’ll be able to get at this stage will be far less attractive than if we fund ourselves to at least the point where we can demonstrate the potential, and understand the likely demand. Investors are mostly impressed by scrappy execution.

This often creates a Catch-22: we need investment before we can afford to leave our day job, but we need to leave our job before investors will take us seriously.5 I don’t have an easy solution, I’m afraid, but know that the best founders somehow find a way to make it happen.

🍸 Mojito Island

Humans are generally not built to derive sustainable happiness from sipping mojitos on a picturesque island somewhere in the Pacific. Once you've tasted the sweetness of a dedicated purpose, it's near impossible to be content just sitting on the sidelines.

Kiwi business people are sometimes criticised for a lack of ambition — selling out once they have enough to buy a bach, a boat and a BMW.

I agree we should all aim higher than this, but I don’t think this means a private jet or super yacht instead.

If we measure ourselves based on how many expensive toys we can buy, we’re never going to be satisfied.

The reason is simple: there is always another level above – a more expensive car, a bigger house, a longer race. As soon as we have achieved something, we quickly normalise it and start to take it for granted. There is nothing so amazing that we can’t get used to it. Then we start to compare ourselves to those who are slightly ahead of us. Our appetite is always slightly bigger than our wallet.

To make this worse, if we’re lucky enough to be part of something that is successful, the first thing people ask afterwards is, “What are you going to do next?” That can weigh you down, take my word for it! 6

So it pays to think about what you care about, have authority over and are prepared to take responsibility for.

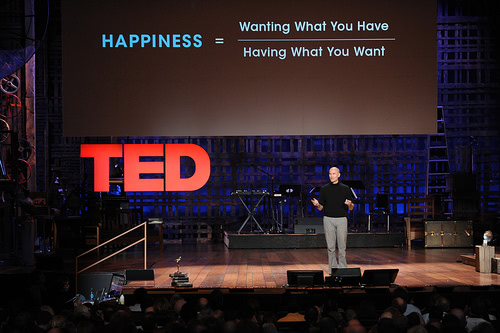

Consider this formula, from Chip Conley’s TED Talk:

How much time do we spend on each part of that equation? Those who understand how fractions work realise that the idea is to focus on increasing the numerator (on the top) not the denominator.

It’s hard to describe how much better it is to work on something that we care about, unless we’ve experienced it ourselves. It’s not a factor of two or three times better, it’s more like 100 or 1,000 times. To really understand this, go and work for a large corporate for a while.

Likewise, once we’ve been part of something as exciting as a startup that has momentum, and the rewards that come from that, sitting on the sidelines is going to feel like a step backwards. Even the biggest boat we can buy probably won’t compensate.

So, enjoy the walk. Think about why we’re doing all of this in the first place. If we’re lucky enough to work on a new venture and create our own job, appreciate the opportunity and try to enjoy it. Financial rewards are a way to keep score, but don’t get too hung up on them. Even if we do all of the above, it still may not work out the way we hope.

All Together Now

So, in summary:

Build a team – probably generalists to begin with, but with a diverse range of experiences and perspectives.

Choose carefully – we need co-founders and investors who will stick around and help us push it along when (not if!) the going gets tough.

Prepare for lots of the initial assumptions we make to be wrong.

Listen carefully and respond quickly with changes where needed.

Be brave and talk to everybody who can help us shape the idea.

Spend our limited time and money on increasing the chances that we’ll actually succeed, rather than wasting them on preparing for success which may never eventuate.

Work out what actually fuels our growth and how to tell our story in a way that spreads.

Understand there are lots of different ways to grow a successful business. We need to choose the one that is appropriate for us. Perhaps that means taking investment to grow as fast as we can, or perhaps that means aiming for profitability sooner and growing at the pace that allows.

Be realistic about the value of what we’ve created, and honest with those that we’re bringing along for the ride.

Have the right end in mind.

Get started!

When you describe a startup like this it doesn’t sound at all like a fairytale. But better, I think, that we go into this sort of thing with our eyes open.

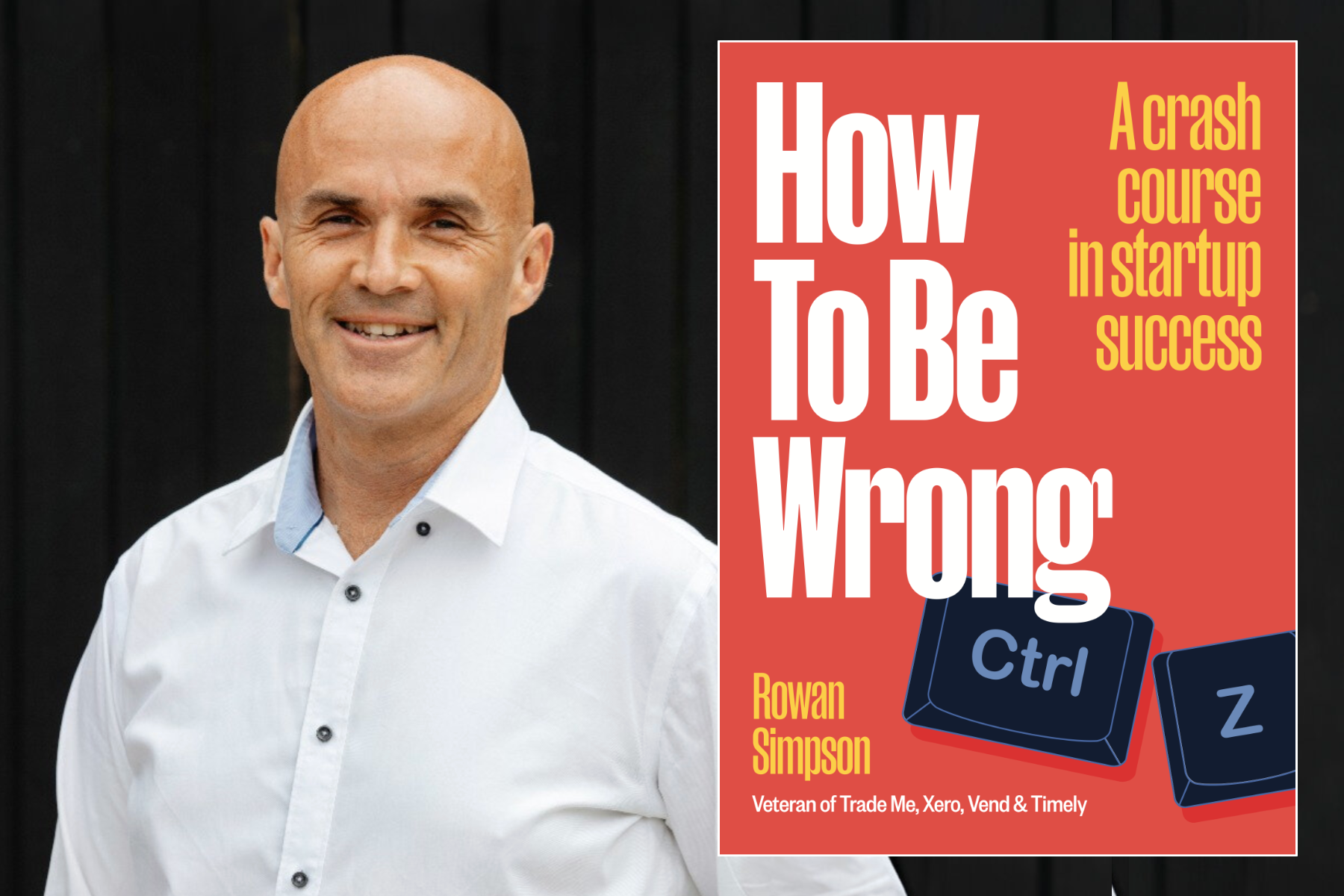

This is based on a talk I gave at Summer of Tech. It was first published in Idealog Magazine.

-

Credit to Nat Torkington for this insight. ↩︎

-

Source: Mike Carden ↩︎

-

Credit to Seth Godin for this phrasing. ↩︎

-

This is especially true for founders from under-represented groups, who often struggle to find any investors, despite the evidence showing that in many cases these are the best founders to back. Eventually the market will catch up on this, but that is no consolation to those founders struggling to get support in the meantime. ↩︎

-

Occassionally founders who have sold their business say this out loud:

For example, Joshua Schachter wbo sold Delicious.com to Yahoo, later said:

I wish I had not sold … The cash and freedom do not even come close; I would rather work on a big, popular product

The sale of Delicious came full circle years later when Joshua’s friend Maciej, founder of competitor Pinboard, purchased the site and shut it down. ↩︎

Related Essays

Product Management

Try to complete as many loops as possible, getting a little bit better each time.

Scar Tissue

Working on a startup is much more like racing a BMX bike than riding a roller coaster.

Continuums

What do we gain and what do we lose when we treat the world as binary?

Monochrome

What can rugby teams and rowing squads teach us about building and managing diverse teams?

Inconvenient Values

Why is it so hard to articulate and document shared team values?

Getting Lucky

How do we break luck down into its component parts, so we can create luck for ourselves and for others?

Buy the book