Cofounders are for a startup what location is for real estate. You can change anything about a house except where it is. In a startup you can change your idea easily, but changing your cofounders is hard.

Every founder who has ever asked me for advice about their startup is familiar with my favourite question: What’s the constraint? It’s a great way to identify the most useful things to talk about, to dig into the specific areas of the business and to understand what could unlock growth.

More often than not the answer is related to people - i.e. how to manage the existing team so they perform to their potential, and how to grow the team without wrecking the culture. This same idea applies at the ecosystem level. How do we identify and remove the systemic constraints that make it difficult for ventures to start and scale?

The talent trap

The whole time the shape of the startup ecosystem in New Zealand has been distorted by the misconception that capital was the constraint, many great founders were out there raising millions of dollars to fund their growth, including pretty much all of the successful companies we celebrate. When we ask them what’s holding them back, nearly all point to the challenges of finding and keeping great people in their team.1

Every one of the “hundred inspired entrepreneurs” that Sir Paul Callaghan was hoping to uncover themselves needs to hire hundreds (maybe thousands?) of qualified people to help them grow their businesses. But, more and more, high-growth startups in New Zealand are either forced to poach staff from each other or hire offshore. That’s not a sign of a vibrant ecosystem. How could we remove that constraint? Where else could these people come from?

We could train them. While the need for more qualified people to work on these businesses has been well sign-posted for many years, you would not be able to tell by looking at the statistics. To pick just one data point, in 2023 only 2,740 domestic students graduated with a bachelor’s degree in science, with a corresponding 1,205 in information technology and 590 in engineering.2 That number doesn’t come close to meeting current demands for recruitment. And it’s not just technical graduates that are scarce. We are also drastically short of sales and marketing people with experience selling the type of products that startups here are building.3 We urgently need to inspire more students to pursue these types of careers.

Another obvious potential solution is to convince qualified people from overseas to relocate. Our global reputation as a place to live and work has probably never been better, but the key to unlocking this at scale is our immigration settings and there is scant evidence that any of our attempts to date have addressed the constraint we’re talking about, including ultimately fruitless schemes like The Edmund Hillary Fellowship. The idea was smart: target younger founders with a greater appetite for risk, who don’t qualify for other visas (mostly because of the financial criteria).4 The results seem mixed. As always, when success depends on picking winners the outcome depends on who we allow to do the picking.5 Many of the fellows seem to have been selected for their current celebrity rather than their deep commitment to living in New Zealand and contributing directly to local ventures.6 That seems like a big missed opportunity. If we are not clear about who we intend to help, what constraint they have and how we hope to reduce or remove that constraint, then we will struggle to demonstrate any impact.

Or, consider the special visas available to so-called “active investors”. We overemphasise the lifestyle that all of us who choose to live here enjoy, and so fall into the trap of promoting ourselves as a comfortable place to retire for people who are at the end of a successful career, rather than a place that attracts people who are still hungry to build new businesses.7

Next time you read that New Zealand needs to incentivise successful entrepreneurs from overseas to relocate, I’d like you to imagine we are the owners of a second-division French rugby club, who continue to believe that the key to success is signing another soon-to-retire All Black or Springbok.8 Is that really the way to transform the future?

A third option, that doesn’t get anywhere near as much airtime as those previous two, is rescuing existing New Zealanders from corporate servitude. I joke, but only a little. Once people have experienced working in a high-growth company there are very few who choose to go back into a corporate or public sector job. And those who do often don’t last long before they jump again into an environment where the outcome is far less certain and so their ability to influence the outcome and benefit from that is so much greater. It’s addictive.

Why don’t more people do this? I wonder if the dominant narrative about startups is again partly to blame. If you’re working in a secure job and everything you see about startups looks like a reality television show – incubators and accelerators and demo days and startup weekends – then it’s easy to assume it’s all a bit of a game, and not a serious career option.

To convince more people to take the risk on a role in a startup we have to do a better job of demonstrating the opportunities that exist in actual high-growth and early-stage startups, rather than just banging the ecosystem drum louder and louder.

If you’re one of these people: be more curious. There are so many interesting and different jobs available at companies that you’ve probably never heard of. The biggest problem they have is attracting people with useful experience to join their team. Because they are growing quickly the range of things you’ll be exposed to will blow your mind wide open, and with that come amazing career opportunities. What have you got to lose?

Last but not least (probably most) we can all do a much better job of diversifying. It’s difficult to claim that our biggest constraint is recruitment when our startup teams are filled with predominantly young white bearded men.

This is a pattern that is repeated too often: the first few people to join a startup team all look quite similar to each other. The reasons for this are usually innocent: they normally know the founder and might be the only people prepared to take the massive risk involved in being the first believer. Then, when the team expands, those people hire their friends. When operating at pace this can seem like the easiest option, and it’s a common mistake. However, once that pattern has been repeated a few times the result is a monochrome team and a culture that is unlikely to appeal to anybody who doesn’t fit that mould in the future.

Successful companies tend to have much more diverse teams. That’s not an accident or a coincidence.

There are two often overlooked uncomfortable truths about diverse teams: they are much harder to manage and they are harder to build. Those who worry that a diverse team will break the system that currently works might be right. But sometimes we have to step back in order to escape a local maxima.

We understand this when selecting rugby teams. A team of 15 locks would dominate the restarts and lineouts but would be destroyed in the scrum and would struggle with goal kicking. A team of 15 outside backs would never get the opportunity to use their skill running with the ball, because they wouldn’t create the foundation in the forwards. A great rugby team has players that complement each other. This is why we never think of the three front-row forwards who are selected as taking opportunities away from outside backs. It’s not about “selecting on merit”. There are multiple jobs to be done and different people are more suitable for each of those. The optimal team is a mixture.

At capacity?

Despite all of these challenges, it is a hopeful time. I can tell lots of stories of astonishingly competent people who have started or worked on amazing ventures. I’ve been incredibly fortunate to have some of them as colleagues over the years. Some of them were born and educated here. Some have come from overseas to base themselves here. They make this a better place. But there are just not enough. We need more. We need many more. Until then, this will continue to hold us back from growing more of these types of businesses, with all the collective benefits that would bring.

If we’re going to make the most of our large and underpopulated islands, we need to be honest about our actual constraints.

-

This tweet of mine, from 2014, remains frustratingly evergreen:

↩︎Stop thinking that capital is the constraint to more high-growth kiwi companies. Every company I’m invested in can’t hire enough people.

-

“Students gaining qualifications from tertiary education providers: 2014–2023”, Education Counts, Ministry of Education. ↩︎

-

Detailed analysis on this would teach us a lot. For example, tracking how the increase in graduates across these categories has flowed into employment, and specifically into which companies (are these people taking jobs in high-growth businesses or more mature businesses)? ↩︎

-

The cabinet paper making the case back in 2015 admitted that the pre-existing Entrepreneur Visa, while “working well”, wasn’t “designed to bring in the more innovative, global entrepreneurs needed to support the growth of New Zealand’s innovation system”.

(This also begs the question: what was it designed to do, and on what basis was it working well?)

Global Impact Visa Program Briefing Papers, Stuff (via OIA request). ↩︎

-

Global Impact Visa Evaluation, Year 3 Final Report by Martin Jenkins, MBIE, March 2021. ↩︎

-

The curious world of New Frontiers by David Farrier, The Spinoff, 29th January 2020. ↩︎

-

This scheme was temporarily suspended during the COVID-19 border closures. News that the scheme was opening up again provided welcome relief to real estate agents in Queenstown, I’m sure. ↩︎

-

Does importing foreign players at the end of their career even work for sports teams? I can’t find any data for rugby clubs specifically. Research shows foreign players do improve short-term results for European football clubs, but it is financially unsustainable unless the owner is a Russian oligarch or Saudi prince. And it also reduces opportunities for local players. ↩︎

Related Essays

Monochrome

What can rugby teams and rowing squads teach us about building and managing diverse teams?

Machines & Phases

There are so many different ways to measure a startup. It’s easy to drown in metrics. How do we separate the signal from the noise?

Break Points

We don’t always prepare for growth that happens suddenly, in bursts.

Building An Ecosystem

How can we build an ecosystem of innovative technology startups in New Zealand?

The Triple Threat

There are only three ways to be wrong about our impact: neglect, error and malice.

Derivatives

How do all of the programs designed to support startups actually help?

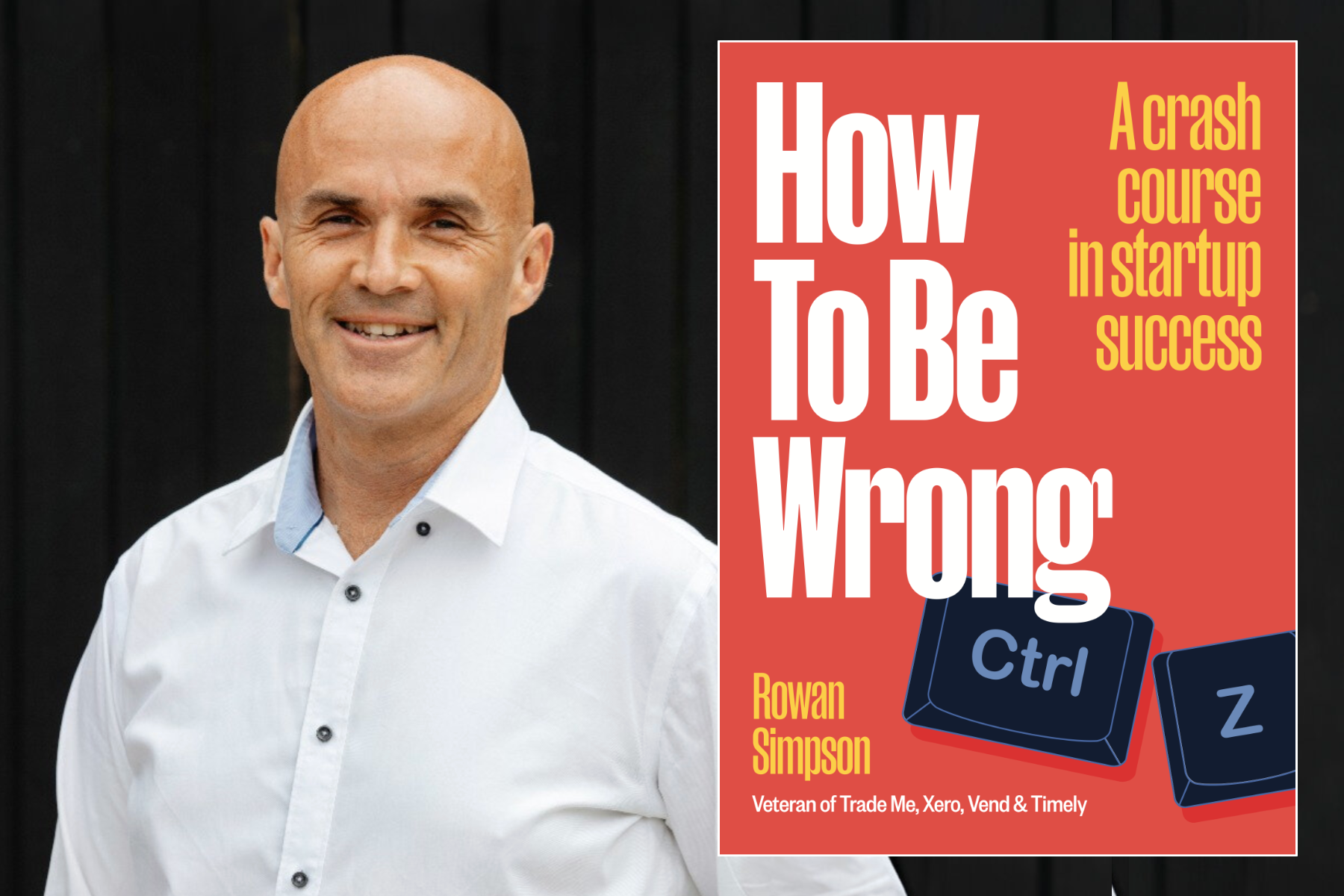

Buy the book