Just as startup stories tend to skip over the dark and doomy days, they almost invariably focus on an individual. That’s another mistake.

In 1997 Apple leaned into this stereotype when they launched their new slogan: Think Different.1 The television advertisement featured personalities like Albert Einstein, Amelia Earhart, Pablo Picasso and Mahatma Gandhi. The voice over crescendos:

Here’s to the crazy ones.

The misfits. The rebels. The troublemakers.

The round pegs in the square holes.

The ones who see things differently.

They’re not fond of rules.

And they have no respect for the status quo.

You can quote them, disagree with them, glorify or vilify them.

About the only thing you can’t do is ignore them.

Because they change things. They push the human race forward.

While some may see them as the crazy ones, we see genius.

Because the people who are crazy enough to think

they can change the world, are the ones who do.

For Apple, this was a shot across the bow of IBM whose long-standing motto was simply: Think. Steve Jobs had recently returned as CEO of the company. In hindsight, it may have marked the turning point ahead of the launch of products which have changed the world: the iMac, the iPod and the iPhone.

While it is a powerful piece of marketing, that slogan never really resonated with me. I didn’t see myself in any of those traits: I’m not a rebel. I’m not a troublemaker. I much prefer to understand the rules so I don’t break them. These so-called “crazy ones” are all people who don’t fit the mould. I’m much more mould shaped – at least on the outside – a round peg in a round hole. That doesn’t mean I accept the status quo. I also want to change the world, at least a small part of it. But I’ve learned that changing the world is a team sport.

It takes two (probably more)

The Think Different campaign put the spotlight on specific individuals, and in the process overlooked all the others who contributed. This is a repeated pattern.

Whenever I see a flamboyant or high-profile “crazy one” I like to look for the associated “quiet ones”. The co-founders. The collaborators. The ones who see things as they are. They are often hiding in plain sight, working behind the scenes, helping the crazy ones with their rough edges. They are nearly always overlooked, underestimated and ignored, but their contributions to creative work are vital to any success.

Perhaps the canonical example is Bernie Taupin, the songwriter best known for his 50-plus-year collaboration with musician Elton John. He wrote the words for nearly all the hits that are typically associated with the brilliant singer.

Or Charlie Munger, the business partner of Warren Buffett from 1978 to 2023. Buffett is widely acknowledged as “the best investor in the world”, but most of those investments were made together with his lower-profile billionaire collaborator. Buffett himself was clear. In 2021 he told CNBC: “He makes me better than I would otherwise be and I don’t want to disappoint him.”

Or Ted Sorensen, the speechwriter for President John F Kennedy, as well as one of his closest advisors. Kennedy is remembered for his stirring oratory. Sorensen wrote many of the famous lines, including “Ask not what your country can do for you, ask what you can do for your country” from Kennedy’s inaugural address, and “We choose to go to the moon in this decade and do the other things, not because they are easy, but because they are hard” from the speech in which Kennedy announced his intention to land a man on the moon before 1970.

There are so many others: Eric Bina, the co-founder of Netscape and inventor of the web browser, whom you’ve likely never have heard of; Gene Kranz, the flight director for NASA throughout the Mercury, Gemini and Apollo space programmes; and Tenzing Norgay, who may have been the first person to the top of Mount Everest (we’ll never know for sure, because the people involved in that feat all understood it was a shared achievement).

Those examples are all men. But there are many more women who fit this description, whose relative obscurity is exacerbated by sexism.

Such as Susan Wojcicki, who was Google’s first marketing manager in 1999, the product manager behind AdWords (the core of Google’s lucrative business model), and the CEO of YouTube from 2014 to 2023, after leading the acquisition in 2006. Her garage was also the company’s first “office”. She died tragically young in 2024. Throughout her career she remained much less well-known than the founders Sergey Brin and Larry Page.

Or Lise Meitner, an Austrian physicist, who together with Otto Hahn discovered that atomic nuclei could be split into smaller parts, leading to the development of nuclear energy. In 1944 Hahn was individually awarded the Nobel Prize for this discovery.2

Or Camille Claudel, a French sculptor and a student and collaborator of Auguste Rodin, one of the most celebrated sculptors of his time. Her work was often attributed to Rodin, and she struggled to gain recognition as an individual artist. At the Musée Rodin in Paris they now have a whole room dedicated to her work.

Constructive friction

To be fair to Steve Jobs, he understood all this better than most. While he is remembered as a visionary individual, he was more importantly an inspirational leader who built formidable executive teams in multiple companies: Jony Ive, Tim Cook, Phil Schiller and others during his second stint at Apple; and Ed Catmull and John Lasseter at Pixar, for example.

He once told the story of using an old concrete mixer to make polished rocks when he was a kid. Starting with unremarkable pebbles and a bit of grit, they would bounce off each other until they emerged a few days later as beautifully smooth objects. He took this as a metaphor for how teams working together to create new products can use constructive friction to make each other better.3

The myth of the lone genius is pervasive. It obscures the way that any interesting work actually gets done through collaboration and teamwork. Those with the biggest personalities or who make the most noise get the most attention. But don’t let that confuse us about how we can each contribute or about how important it is to surround ourselves with people who can cover the areas where we’re not strong.

In the real world, any team with a dominating leader who insists on being at the centre of attention is like a computer operating system that can only run one application at a time: they can sell to customers, or do support, or build product, or fix bugs, or hire, or fundraise – but only one at a time, and with horrendous context- switching costs.

So, sure, raise a glass to the rebels and the troublemakers. But always keep in mind the lyricists and the lab assistants. Wherever you individually belong on that spectrum there are important jobs to be done.

-

Think Different - Full Version, YouTube. ↩︎

-

This is a repeated pattern: Rosalind Franklin, Jocelyn Bell Burnell, Mary Anning and Chien-Shiung Wu are other examples. ↩︎

-

Steve Jobs’ Rock Tumbler Metaphor, YouTube ↩︎

Related Essays

Rich vs Famous

If you had to choose, would you rather be rich or famous?

People, People, People

Ask the best startups what’s holding them back and they all point to the challenges of finding and keeping great people.

Monochrome

What can rugby teams and rowing squads teach us about building and managing diverse teams?

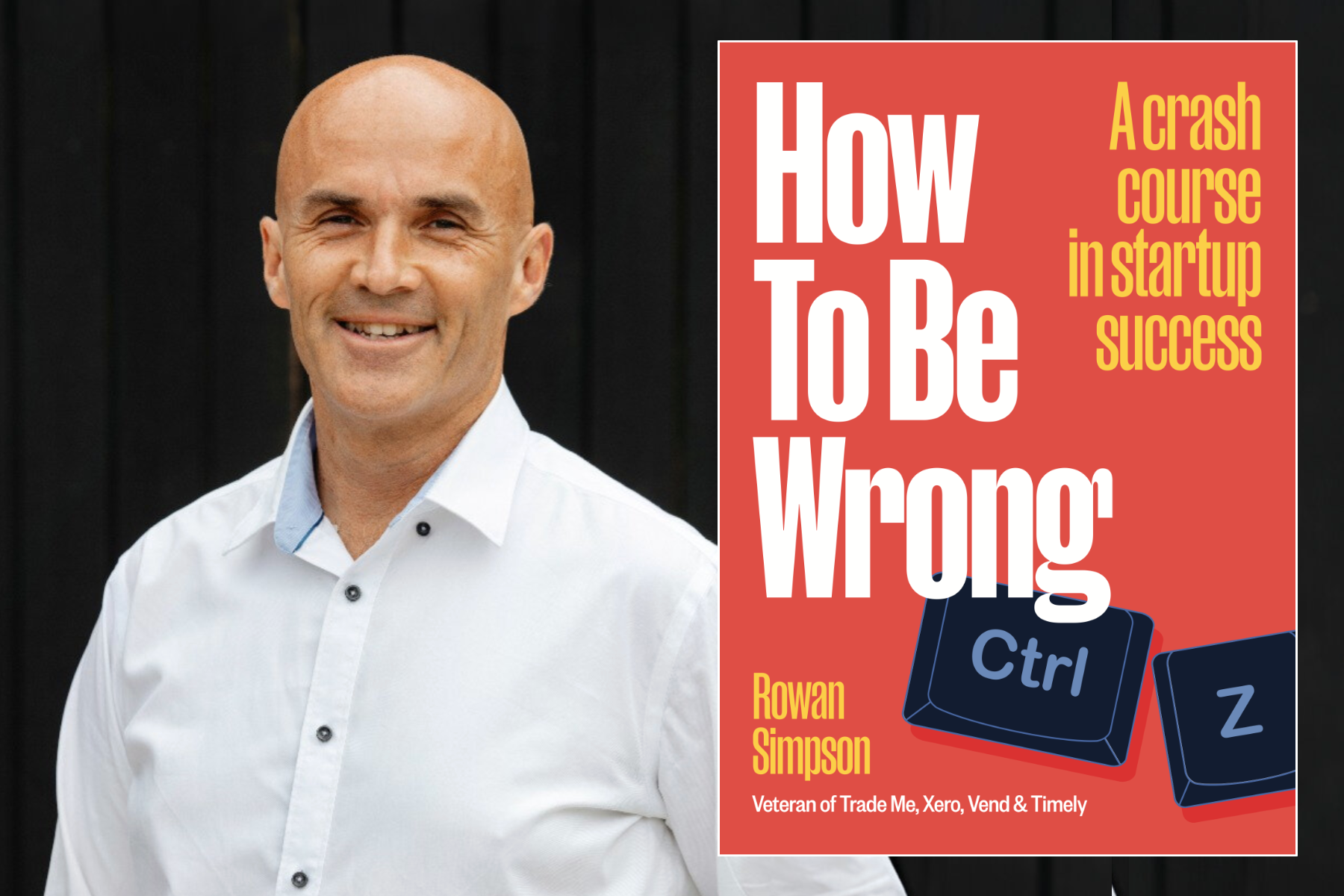

Buy the book