The more slowly trees grow at first, the sounder they are at the core, and I think that the same is true of human beings.

One step at a time

The outskirts of Nairobi in Kenya was one of the last places in the world where I would have expected (somewhat arrogantly) to learn an important startup lesson. But a trip in 2009, shortly before I started working on Vend and Timely, ended up totally changing my mental model of how to start and how to scale a business.

We spent a morning with Jay Kimmelman from Bridge International Academies Like many founders I’ve met over the years, he was excited to describe the business opportunity he was working on and to demonstrate some of the progress he had made. Remarkably, his “venture” was a network of primary schools he and his team were building from the ground up in the heart of one of the largest slums in the world, an area of extreme poverty, and one of the harshest places you could possibly imagine to start and scale a business, supported by donors like the Gates Foundation and eBay founder Pierre Omidyar.

We started by visiting the schools. It was humbling to see the simple buildings – dirt floors, hand-painted logos on the corrugated metal walls, reinforcing steel in the place of glass to define the windows. It was inspiring to meet the teachers – they were young, well paid by comparison to peers (they received M-Pesa1 credits direct to their mobile phones, a more useful currency than cash) and very motivated to ensure that the students actually learned. Then Jay took us to a nearby restaurant run by an intimidatingly large South African man who served us equally massive steaks for lunch. I could only get through half of mine.

Jay is a no-nonsense person, and my notes from the day are succinct and to the point. He started by describing the curriculum he wanted to teach (effectively the product he was offering his customers):

- Reading with understanding

- Maths

- Critical thinking 2

Then, he listed the unknowns he needed to validate to show that his schools could be viable:

- Economics - can the service be delivered at the required cost point?

- Demand - will people pay?

- Quality - are the education outcomes good?

Finally, and most importantly, he talked about his plan to scale:

- Pilot - first school.

- Replicated - second school.

- Multiple - five new schools at once.

- Many - so many new schools at once that it will fail unless the systems are great.

He described a generic approach to growth that we can apply to many other things. First we solve a problem once. This often requires a remarkable individual and the brute force needed to ignore all of the valid reasons why it’s impossible.3

Then we do it again, to prove to ourselves and others that the first time wasn’t an accident. The second time we see the useful patterns. Then we build a team to do it repeatedly at scale. These team members will be mostly specialists with specific skills, compared to the generalists who get things started from nothing. We need to choose carefully because we soon discover their true character when the going inevitably gets tough.

Finally we create a repeatable and self-sustaining system that doesn’t rely on a superhero manager or context. We need to prove we can do it at a scale where it is beyond the ability of one amazing person, or even a single team of amazing people, so it can only work if the systems are rock solid.

This is a common progression: first we learn to crawl, then walk, then run. However, we’re often tempted to skip the intermediate steps. We jump straight to trying to solve the problems of scale and repeatability, without first proving that we really understand what it takes to do it once, then twice.

It should be no surprise that the things we create that way are brittle, prone to failure and seldom achieve their potential. As impatient as we are, we need to take the time to really absorb the lessons from each stage, because they create the platform for subsequent stages.

-

M-Pesa is Aamobile-based payment system, used as a de facto banking system by millions of people in Africa.. ↩︎

-

Benedict Evans, Twitter, 22 January 2015:

↩︎The better you understand a sector, the more you know all the reasons why it’s impossible to disrupt it.

Related Essays

Unit of Progress

Be specific: Where are we going and what will it take to get there?

Hockey Stick Growth

It takes a long time to become an overnight successs. But to get there we need to be growing from the beginning.

Break Points

We don’t always prepare for growth that happens suddenly, in bursts.

The Plunge

Why do the most interesting bits of startup stories always get airbrushed out?

How to Get Old

We only get to be each age once. How many will we waste trying to be something that we’re not?

The Triple Threat

There are only three ways to be wrong about our impact: neglect, error and malice.

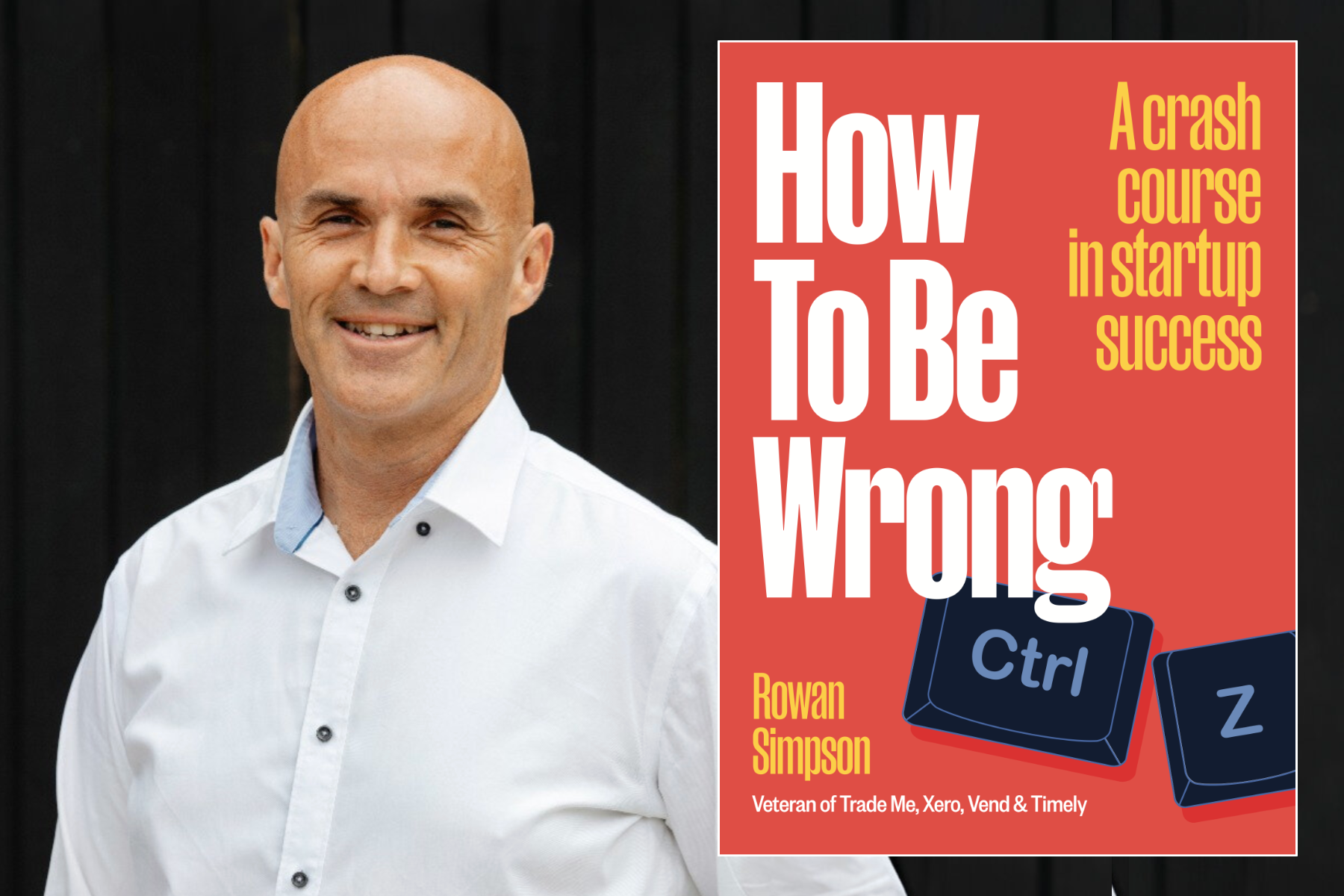

Buy the book