When we talk about “values” it is usually shorthand for four different questions that the team need to answer:

- Mission - why do we exist? 1

- Values - what do we believe?

- Vision - what could we be?

- Culture - how will we work together?

I’ve helped a number of startup teams try to articulate and document their shared values. It’s a humbling, invigorating and heartbreaking exercise. Humbling, because we quickly realise how difficult it is to succinctly describe what always starts out feeling self-evident. Invigorating, because stepping away from the grind of business-as-usual to consider the “why” is an excellent way to remind ourselves that the pain is worth the gain. But perhaps most importantly heartbreaking, because when we try to describe what we stand for we find so many of the words we use are vacuous…

Disrupt. Empower. Enable.

Beautiful. Easy to use. Loved.

Impactful. Purposeful. Positive.

Customer-centric. Design-led. Fact-based.

Leadership. Collaboration. Innovation.

Integrity. Accountability. Diversity.

Simple. Powerful. World class.

Here are three critical questions that help filter the signal from the noise…

1. Who believes the opposite?

First, flip any proposed value around and see if it still makes sense. If we think it’s unique to build a product that’s beautiful and easy to use, we should ask who is trying to build something ugly and unnecessarily complicated. If we say that our customers come first, we need to point to teams who genuinely don’t care and put them last. If we say our policy is “don’t be a dick” (and think that’s sufficient) it’s useful to consider the team who are intentionally dicks and what advantages that might give them.

If we can’t find anybody who believes the opposite then we likely haven’t identified a useful value or a competitive advantage. We’ve just uncovered the table stakes. The opposite of a useful value is often itself a useful value. Explicitly stating the opposite value often makes what we’re trying to articulate clearer and easier for others to understand. Think about algebra. If we have the same value in the numerator and denominator then they cancel each other out.

XY / Y = X

It’s not enough to believe in Y. Everybody believes in Y. We need to find the X. That is, the differentiator that sets us apart, makes us memorable and remarkable.

If we want to be right, we have to understand how to be wrong.

2. Is this a hope or a method?

Next, ask if what we’re describing is a destination or a route. Everybody thinks senseless meetings waste everybody’s time. Very few teams find a way to work together that eliminates the need for them. Many say they want to hire a team of people smarter than them. Few can articulate the specific reasons why great people will be tempted to join their team or have the recruitment process that will attract anything other than a bunch of people who look and behave a lot like the existing team does.

To usefully articulate what we want to be, we need to go beyond describing the result we’d like (the destination). We need to own the process we’ll use (the route). Ultimately our values are not what we write down, they are what we do every day. The way we act (team culture) trumps the words we say every time. Diet is not something we’re “on”, it’s what we consistently put in our mouths. Philosophy isn’t something we read, it’s the way we live.2

3. What does this cost?

Finally, we need to find and accept the downside. Document the “however…” They’re only really our values if we stick with them despite the costs.3

We often worry more about appearing not to have problems than about achieving outcomes, and so don’t recognise when our own mistakes or weaknesses cause the problems we have. Our defining characteristics are usually also our biggest vulnerability.4 Understanding those weaknesses is much more useful than listing our strengths. Maybe we’re relentlessly positive. Everything is awesome. As a result, we’re probably unlikely to hear negative or potentially constructive feedback because nobody ever wants to be the first one to call the emperor naked. Maybe we’re loyal. As a result, we hold grudges, and can be slow to forgive or forget people who have treated us poorly or to acknowledge where past friendships have deteriorated to the point where they would be most usefully abandoned. Maybe we’re fastidiously fact-based. And, as a result, sometimes over-analyse and get bogged down in difficult decisions, rather than relying on instinct to make good fast choices when needed.

Again, if we can’t quickly identify the downside then we probably haven’t found a particularly useful differentiator – because if there is only upside then why wouldn’t everybody do the same thing?

If we can articulate what our values will cost us, and accept that we are prepared to bear that cost, then we’ve probably found something that is really important and uncommon.

Asking these three questions makes the whole process of articulating our values much more difficult but ultimately produces better results.

That’s worth it, right?

-

I love the formulation suggested by Kevin Starr from the Mulago Foundation:

↩︎Your mission statement should be nine words or less: verb, target, outcome.

-

How to Start a Cultural Revolution, Ben Horowitz at StartupGrind, YouTube, 2016. ↩︎

-

Kim Goodwin, Twitter, April 2019:

↩︎They’re not really values unless you apply them when it’s inconvenient.

-

Is Your Greatest Strength also Your Biggest Weakness?, The Colourful Principal (via Internet Archive), 16 November 2013. ↩︎

Related Essays

Monochrome

What can rugby teams and rowing squads teach us about building and managing diverse teams?

Anything vs Everything

How do we choose what to focus on, and have the conviction to say “no” to everything else?

How We Win

How well does your team understand your plan to win? When was the last time you wrote it down or said it out loud?

Most People

To be considered successful we just have to do those things that most people don’t.

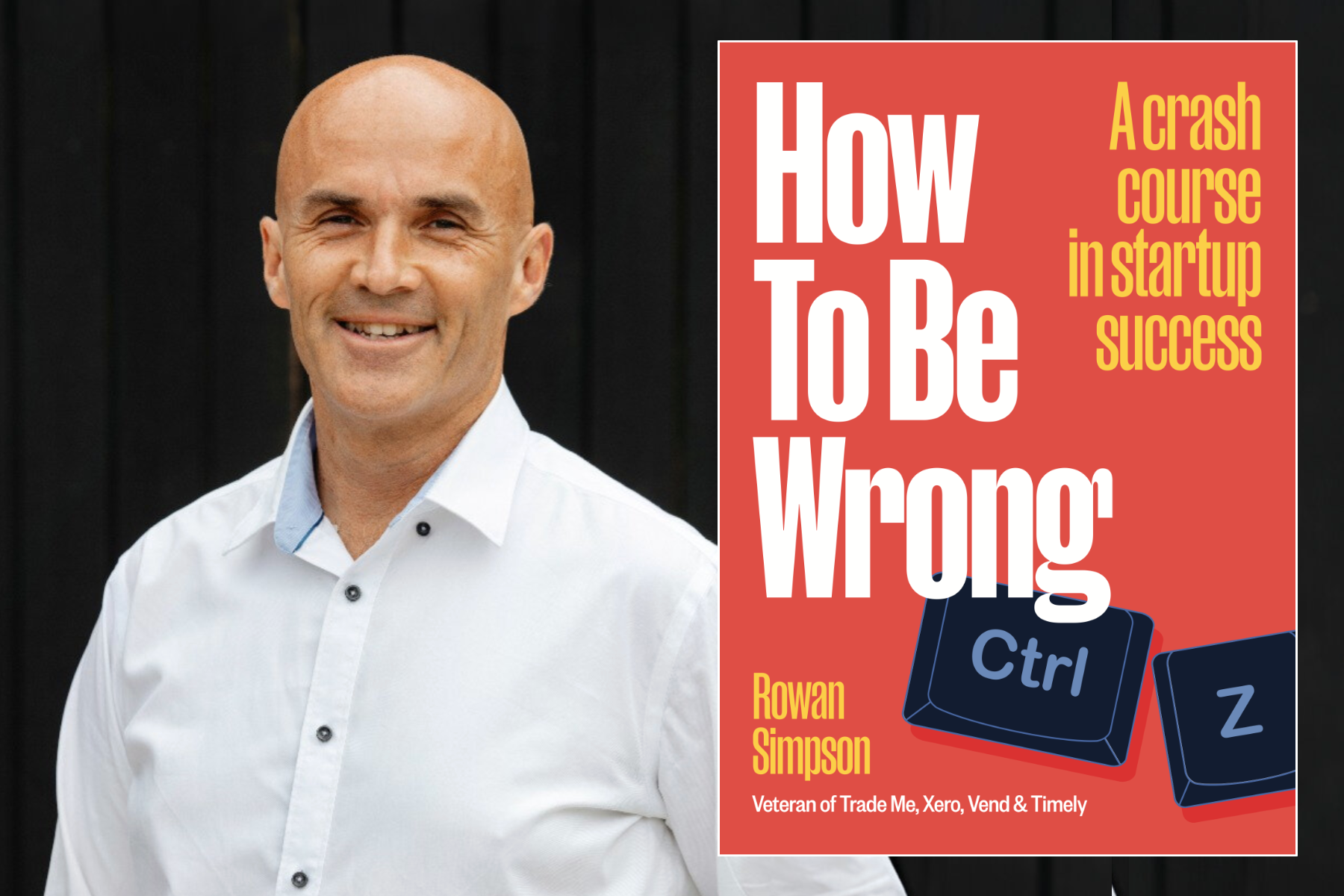

Buy the book